When I read a work of literature in my downtime, I tend to stray away from poetry. Personally, I’ve always held the assumption of poetry being abstract and meant for modern philosophers who could waste their time on figuring out the meaning behind every other word that rhymed in a stanza. I am aware that this is a weird mentality to have, but I was ignorant and chose not to educate myself to appreciate the art behind poetry. After reading through the packet of poems Professor McCoy gave us in class, I’ve come to realize that poetry doesn’t have to follow the typical sonnet format or rhyme in order for a reader to appreciate the story for its worth. I had also learned more about my culture in the sense that Caribbean writers had a space to exist in during a period of history when many voices were ignored.

I am so glad that it was brought to my attention that Claude McKay, a Jamaican writer and poet during the Harlem Renaissance, had existed in such a rough time in America’s history. McKay proved himself as unapologetically black in many of his works, including Home to Harlem, Songs of Jamaica, To the White Fiends, and many others. This young man from Kingston wrote in an academic setting that many at that time didn’t believe he belonged in, but his writing showed otherwise. I will say that I applaud McKay for proving his worth by writing about personal accounts in a poetic manner when critics and racists alike belittled him. What really made McKay a well-known name not only during the Harlem Renaissance in New York City but internationally as well is his poem, If We Must Die.

McKay’s poem If We Must Die reads as such:

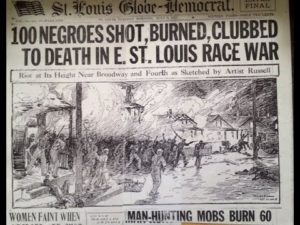

At first, reading this poem sounded like a unifying rally call for people to fight back against some oppressive force. After doing some research, I found out that McKay wrote this piece for that exact reason. His poem was released during the Red Summer of 1919, in which multiple race riots broke out across the country, causing harm or death to hundreds of innocent African-Americans. McKay, being the revolutionary writer that he was, took this devasting moment in America to encourage people to not give into the unjust powers that be and to fight back nobly.

Not only is McKay’s poem powerful, but his boldness to have his work published at a time when people would’ve (and probably did) threat him or cause him harm. He didn’t care about the repercussions he could’ve faced from his poem. What mattered to McKay was to reassure African-Americans at that time to not lose faith in the fighting cause, even if things weren’t looking promising in the end. Also, I find it fascinating that McKay’s poem is timeless in the sense that it can be applied to other revolutionary moments in America’s history, such as the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Lives Matters Movements, and other contemporary social movements led by newer generations.

If it weren’t for Claude McKay being brave enough to write about a time when the odds were unfavorably against black citizens, then no one would’ve appreciated his work. Nor would anyone be able to reflect on how dangerous it would’ve been for him to voice his opinions at this time. Also, if it weren’t for Professor McCoy for handing out that packet for our class to take the time to read through each poet’s story, then I would’ve never learned to appreciate and respect the personal reflections that poetry can offer.