By Ashley Boccio

When we look at ourselves and each other, whether we like to admit it or not, we tend to categorize and create groups based on image. For example, when you first meet an individual you may notice if they are blonde, brunette, or ginger. A harmless observation, yet this recognition of difference almost always goes beyond just hair color. Delving into the concept of “race”, a human made ideology not based in biology, we often use stereotypes to unfairly group individuals and make initial judgements on their character. Throughout history, various groups have been persecuted, exploited, enslaved, and ridiculed based solely on race. With this unfair judgement there comes an unwarranted justification for horrific acts without consent or reason. This conversation opens up the platform to the question: how can we learn from our mistakes and atrocities of the past to better ourselves as a society in the future? Although the past may be grim, it is important to dive into the truth on what really happened in order to better understand today’s social dynamic and how if affects our progress today. My personal goal for this course is to learn about and discuss these overarching ideas of consent, race, and prejudice, so I am able to recognize their place in modern society.

To channel our discussion, we can begin with looking at the medical field, and it’s history with the social constructs of race and consent. In Harriet Washington’s book, “Medical Apartheid”, she fearlessly exploits the medical field for their atrocities with involuntary medical experimentation on African Americans. This forced experimentation had gone largely undiscussed for decades and was avoided by almost all in the profession. In reading her work, it is evident as to why a majority of African Americans today have an innate fear and distrust for the medical field; often referred to as “iatrophobia”. In Washington’s initial introduction, a line that truly stuck out to me occurred between her and a colleague. In this conversation her coworkers states: “Girl, black people don’t get organs; they give organs.” A statement that sent chills down my spine, helping me to recognize the gut-wrenching fear and stigma that has followed an entire profession. It is evident that there is a large disconnect based in fear between medicine and an entire group of people. A sad truth, as the medical field can be used as a force of good and healing, and should not be feared in modern society. Even Washington makes it entirely clear that she herself is an admirer of the medical field and the profession, stating that she remains to have full faith in the field and its ability to change and progress for the better: “I am an admirer of medicine, and when not working alongside physicians in hospitals, I have spent decades profiling, describing, and analyzing medical advances and the remarkable people who have made them.” However, despite her love for the field, Washington strongly believes that the stories of these abused individuals need to be heard in order to prevent anything of such horrific scale from reoccurring in the future, even if it means exploiting various medical studies of the past. In doing so it is her goal to break down the barriers between African Americans and the American health-care system in order to benefit both parties in the future. Washington’s take on breaking down the dark under shadow of racism in the medical field is pertinent to the larger discussions being brought in under this courses epigraph.

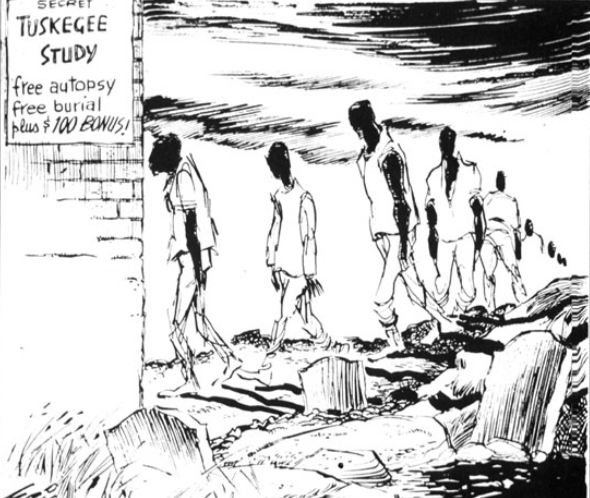

In conversation about consent it is impossible not to look at Washington’s exploitation of the infamous “Tuskegee Syphilis Study” of 1932. The study is known for its barbaric practice and experimentation on young African American woman used to gain further information in the gynecological field. These women against their will were subject to surgeries that mutilated their bodies and caused them excruciating pain, all in the name of medical research. Due solely to their race, these individuals were pushed down in society, and never given opportunities to educate themselves or have a fighting chance at being able to escape studies of this nature; their bodies repeatedly subject to tests without their consent, or knowledge of what was going to be done to them. Even in today’s society, it remains a prevalent issue as to what women can and can’t do with their bodies. Consent, and lack of it, has been a large overarching theme throughout history, and it is clear that its discussion is essential to recognizing and breaking down its negative effects on society today.

Why is it that in our past we have allowed different groups of people to be subject to such horrendous treatment just based on a construct that we ourselves have created? And how can we possibly learn from this? In this course I hope to find the answers to these questions as we read different sources and discuss these difficult subjects. In Geraldine Heng’s book “The Invention of Race in the Middle Ages” he states, “So tenacious has been scientific racism’s account of race, with its entrenchment of high modernist racism…”. A great conclusion to our discussion as it en-captures the hard truth that racism, lack of consent, and prejudice have been the under-belly of our society for thousands of years. It is essential that we can recognize its darkness in order to remove it from our modern dialect and practice. When looking at today’s society it is important to frame our thinking as Washington has in her book. Although there are several horrors, in these horrors there are lessons to be learned. And that’s where I believe this course’s heart lies: in delving into the grit in order to understand how to work towards a brighter future. We can’t expect to change for the better as a society if we do not even know everything we need to re-evaluate and change.