When Dr. McCoy gave the suggestion for us to look into this topic, I immediately knew I was going to do so regardless of whether or not I wrote it as a blog post. For a while now, flesh has been a recurring topic in my writing, and as a Creative Writing major it’s something I am still exploring through fiction and poetry. However, I have not looked at it through the lens of slavery, which I will try here and now to do.

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word flesh comes from the Old English flæsc, meaning “meat, muscular parts of animal bodies; body (as opposed to soul).” Looking at this root, I am drawn to the emphasis on physical body “as opposed to soul,” as though merely an empty casing. Here, I’d like to draw a connection to the setting of this word within Toni Morrison’s A Mercy, in which the word is spoken within a religious colony. Souls would have been of particular concern for the inhabitants of such a place. In regards to slavery, this reading would have a particular significance, as the enslaved persons are being viewed by the slave owners as “commodities” and less than human.

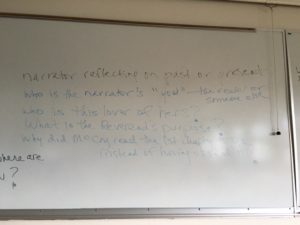

I would then like to draw our attention to the character Jacob who speaks the line “Flesh is not my commodity” in the second chapter. While Jacob regards himself as morally upright and looks down upon the plantation owner D’Ortega’s lavish lifestyle, does his using this term provide us the reading that he may not view the enslaved as full human beings, but rather as bodies lacking a soul? If so, is he then as morally upright as he so thinks?