During the work on our collaborative blog post, my group really ruminated on the use of art as a medium for history. Sabrina Bramwell, specifically, had a lot of really good points about stone eaters as both artistic forms, and as retainers of history and knowledge. I thought I might just expand on the presence of art within Jemisin’s trilogy, as well as its relation to stone eaters, because everything truly blew my mind (LIVE IN ART??????).

Stone eaters are obviously the first example of art in the series. Both Antimony and Hoa appear in the prologue of The Fifth Season (even if we’re not aware of who they are at first), and Hoa is the narrator of the entire story (another point that the reader is not originally aware of). Their presence, although rather peripheral throughout a majority of The Broken Earth, is pivotal to both characters and plot. Not only this, but we learn in the third book that stone eaters quite directly caused the beginning of the fifth seasons. We learn that Hoa, Antimony, and Steel are roughly “forty thousand years old,” (307) as Steel informs Nassun. “Give or take a few millennia.” These stone eaters are the holders of forty thousand years of history. They are also the physical representations of the past. The tuners, as we learn in the Syl Anagist chapters of The Stone Sky, were meant to serve as justification for the genocide of the Niess people. They are a hard contrast to the other people of Syl Anagist. And when they are transformed into Stone Eaters by Father Earth, their immortality as well as their statuesque appearance serve as a reminder of what they’ve done. As Tablet Three, “Structures,” states, “Stone lasts, unchanging” (Obelisk 198).

But there are other instances of art present in the trilogy. One is the smaller scale obelisks that Kelenli shows to the tuners in Syl Anagist’s “museum,” if that’s what we should call it. This piece is another reminder of the Niess, of what was done to them, and why. According to Kelenli, these people were destroyed because “Niess magic proved more efficient that Sylanagistine, even though the Niess did not use it as a weapon” (210). The people of Syl Anagist considered the Niess to be a threat, even if their advancements were only used culturally and artistically. It seems quite ironic, then, that Syl Anagist puts the Niess art on display in their museum, doesn’t it?

Art can also be seen in one of the end-of-chapter excerpts in The Obelisk Gate:

“But stranger than the bones are the murals… one: a great round white thing amid the stars, hanging over a landscape. Eerie. I didn’t like it. I had the blackjacket crumble the mural away.” (279)

The innovator’s account here describes the destruction of art, but also the erasure of a history. The mural depicts the moon. Its destruction is the cutting of one tie to the history of the moon and its loss, and also of a tie to the people who created the mural. While I’ve always been privy to art and its importance in culture and history, I think that Jemisin’s books and my group’s discussion about it created a more palpable opinion on the subject, and also a clearer picture of its importance. And perhaps the most important takeaway from these thoughts is that the meaning of art can be lost if the history attached to it slips into the periphery.

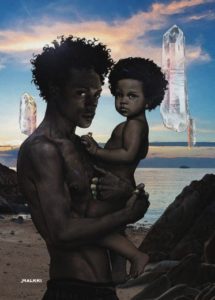

P.S. Since I brought up art, I thought I might show you this gorgeous fan depiction of Alabaster and Corundum that I found on Jemisin’s Tumblr.