Though I am officially no longer a physics major, my life has remained entangled (perhaps quantumly so) with the sciences. It sometimes seems to me as if the sciences refuse to relinquish their hold on me, as this semester I was approached by members of the biology department and asked to serve as a supplemental instructor for General Biology II.

Though I was extremely nervous to start the position, as I am not a biology major, I have grown to love the job, due to the way I am able to make a positive impact on the academic experiences of my peers. Recently, the class has started to learn about muscles and their form and function. During the most recent session, I asked a question regarding typical muscle fiber patterns, which are either pennate or parallel in their arrangement.

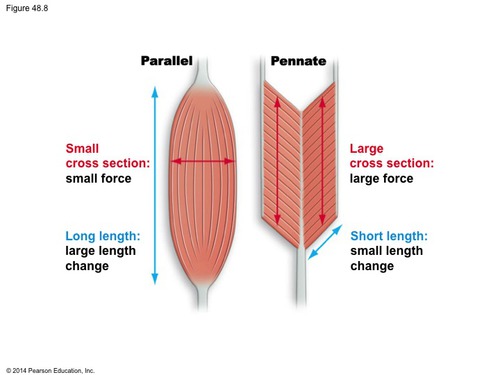

Pennate muscle structure is differentiated from parallel in that the muscle fibers are arranged at an angle to the force-generating axis within the muscle, whereas parallel muscle structure involves muscle fibers that exist in parallel with the force-generating axis. As a result of this differentiated architecture, muscles that feature a pennate arrangement are able to produce more force than those that are arranged in parallel; however, muscles that display a pennate structure are quite limited in their movement.

Returning to the question, it asked which property of muscle was affected by pennate or parallel muscle arrangement. When a student called out the correct answer, “force,” I was struck with an idea for a blog post. Her response conjured an image into my mind: Steve Prince’s linocut, “Flambeau,” and the anatomy and artistry of the woman Prince depicts therein. Particularly, I was reminded of the woman’s legs and arms and the manner in which Prince designed them.

In “Flambeau,” the woman seems to display both parallel and pennate muscle arrangement. For example, her calf is drawn with what appears to be a force-generating axis running down its length and with what could be interpreted as muscle fibers that exist at a sharp, almost perpendicular, angles to the axis. Pennate muscle arrangement seems to exist in the woman’s arms as well, particularly in her shoulders, her deltoids, which are considered multipennate.

What is the significance of Prince depicting muscle arrangement in such an external manner? Is there anything to be gained by investigating the nature of her muscle structure? These questions can perhaps be answered through the process of referring back to the definitions of pennate muscle arrangement and of exploring the context in which Prince created “Flambeau.”

In my interpretation of Prince’s piece, I view the lines adorning the woman’s arms and legs as evidence of underlying muscle structure and find great meaning in my perceived presence of pennate muscle arrangements, particularly due to the woman’s positioning in the piece, as well as the characters and elements that surround her.

The woman appears to be leading a Mardi Gras parade composed of a drummer, a trumpet player, a man carrying a flambeau, and two of the four iconic horsemen that are heavily featured in the breadth of Prince’s work. Together, they move across the panel towards a checkerboard floor that seems to be curling back upon the procession, threatening to impede their progress and perhaps engulf them. In effect, the parade is running out of space, leaving the leading woman to contend not only with the lack of space but the impending crash of the whirlpool taking shape before them.

This is where the woman’s muscle structure becomes significant. Her calves and arms, which bear the presence of pennate muscle arrangement, are poised to protect the procession she leads, as well as hold back the wave that threatens to wash them all away. Just as the upcurling of the foreground has the ability to force the parade backward, the woman also has the potential to harken tremendous force back upon the wave, as a result of the pennate muscle structure I have perceived her to possess.

At the same time, the woman’s pennate muscle arrangement indicates that her muscles would have limited mobility, despite the incredible amount of force they are capable of producing. This limited mobility correlates to the limited space that the parade is being forced to grapple with, as they face a storm coming in from the right and must contend with the dismantling of the space in which they occupy from the left.

Where the curling riptide could represent the powerful, destructive waves of Hurricane Katrina herself, or the man-made chaos of her aftermath, which was itself produced by systemic racism, the woman leading the Mardi Gras parade and her cohorts who comprise it, represent the cultural fixtures of New Orleans that were reborn from the destruction that Katrina caused and from the damage instilled by the worst aspects of humanity which Katrina left exposed in her wake.

Moreover, Dr. McCoy in her essay “Second Line and the Art of Witness,” likens the woman in Prince’s linocut to a Baby Doll, due to the creative and spiritual resistance both the woman in “Flambeau” and the Baby Dolls embody. This resistance, this strength, is seen not only through the Baby Doll’s muscle arrangement, which is latent with tremendous force, but also through the role the Baby Dolls played during the aftermath of Katrina. The Baby Doll’s protective stance, which shields her compatriots from the oncoming wave, invokes the words of Dr. Kim Vaz-Deville, who, during her talk at SUNY Geneseo, claimed that the destruction Katrina wrought played a hand in the restoration of Baby Doll masking tradition.

While the pennate muscle arrangement indicates the strength of Prince’s Baby Doll, which correlates to the creative, cultural force the Baby Doll maskers possess, the lack of mobility latent within pennate muscle arrangement parallels not only the lack of space the paraders in Prince’s “Flambeau” must contend with, but the lack of space the women who would become the first Baby Dolls experienced, as well.

It is important to note that the presence of pennate muscle arrangement only parallels and serves to remind viewers of this lack of space, and does not explain or justify this lack. I add this disclaimer due to the manner in which biology has been historically and inaccurately manipulated to fit the agendas of racist agents. Indeed, it is incredibly dangerous to define individuals and their abilities by their biology, as we, being human, are all much more than the sum of our parts. Thus, while considering the meaning behind the biology present within Prince’s work, one must remain aware of the painful history associated with interpreting biology and use caution while crafting one’s own interpretations. This concept of awareness is extremely important to incorporate and one that is eloquently put by Abby Ritz in her latest blog post.

Furthermore, according to LaKisha Michelle Simmons in her essay, “Geographies of Pain, Geographies of Pleasure,” black women who were living in New Orleans experienced immense pain and trauma in the face of Jim Crow laws and of segregation that “was tied to progress, not simply to tradition.” (Simmons, 32) As a result of such segregation, there were certain spaces black women were not allowed to occupy. This segregation was enforced by white citizens and white police officers who “insulted, excluded, and abused black women and girls,” (Simmons, 32) making sidewalks and other public spaces geographies of pain for these women. As a result of this maltreatment, black women and girls were left with little space where they did not feel vulnerable and where they did not feel as though they had to regulate or control their bodies.

It is in this way that “Flambeau”‘s inclusion of pennate muscle structure simultaneously reminds its audience of the conditions black women and girls faced in Jim Crow New Orleans and of the force these women were able to exert in order to create spaces for themselves where they could, in turn, gather the force needed to become “cultural vanguard[s]”(McCoy, 74) of New Orleans.

Indeed, these women, who faced racism, physical and sexual abuse, as well as constant exclusion, were able to create a geography of pleasure from these hostile spaces through dancing and performing. While performing, whether it was in the streets, at jazz clubs, or at Mardi Gras, black women could reclaim the space they were often denied from by embracing “audaciousness and expansiveness”(Simmons, 37) in their movements. Simmons writes that “black girls also learned of the sensuousness of the performing body, of finding a space to live and let go.” (Simmons, 40), thereby demonstrating the space-creating process of performing. The public dance and performance these women undertook eventually evolved into the Baby Doll masking tradition that still exists today.

Thus, I believe that Prince’s artistic representation of the woman, or Baby Doll, who appears to feature pennate muscle arrangements, is meant to encourage remembrance and appreciation within its viewers for the traumas, challenges, and victories the Baby Dolls, and New Orleans itself, experienced. The pennate architecture of the Baby Doll’s muscles indicates to viewers the protective force and preserving power the Baby Dolls possess, made apparent through their “creative, carnival resistance,” (McCoy, 74) and causes viewers to appreciate the roles the Baby Dolls played throughout New Orleans’ history. On the other hand, the limited space allowed for by pennate muscle arrangement reminds viewers of the circumstances that instigated the Baby Doll masking tradition and thereby serves to remind viewers of the atrocious but actual history of the American South, and of America itself.