Prior to this class, my perception of the line was focused on that in poetry, having taken three poetry workshops almost consecutively within the past two years. What this class offered was a broadening of that focus, to consider different realities and possibilities of the word, both literally and figuratively.

In a poem, a line refers to a single verse, from the Greek word for turn, and multiple lines can refer to a stanza, from the Greek word for room. As such, lines in poetry urge us to consider space and movement. “To truly experience poetry,” says Matthew Zapruder, “we need to try just to be in the poem for a while,” referring to a poem “as something [one is] actually physically moving [one’s] consciousness through, from one line down to the next, and from one room to another, it helps [one] stay there, within what is being said.”

In The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. DuBois also considers the politics and poetics of space, of being oriented and disoriented within a certain plane, to borrow the language of mathematics, of consciousness. In what DuBois calls the “problem of the color line” or the “veil,” also referred to as double consciousness, this figurative line of separation, of constantly seeing oneself through another’s eyes and standards, also becomes a literal, physical line of demarcation through segregation. The demarcations imposed on black people were violent forces upon a person’s consciousness, inflicting both physical and psychological traumas.

In a poetic sense, a line can be broken and, thus, violent, as I mentioned in my first blog post, in the poem M. NourbeSe Philip’s“Zong! #1,” which we read during Dr. Lytton Smith’s first lecture. Multiple consciousnesses in this poem are violently broken, consciousness plotted floating like dismembered digits, with names of victims demarcated under a both figurative and literal “bottom line.” What this disorientation shows is the difficulty of articulation and coherence, the difficulty perhaps of being heard or understood and, thus, silenced.

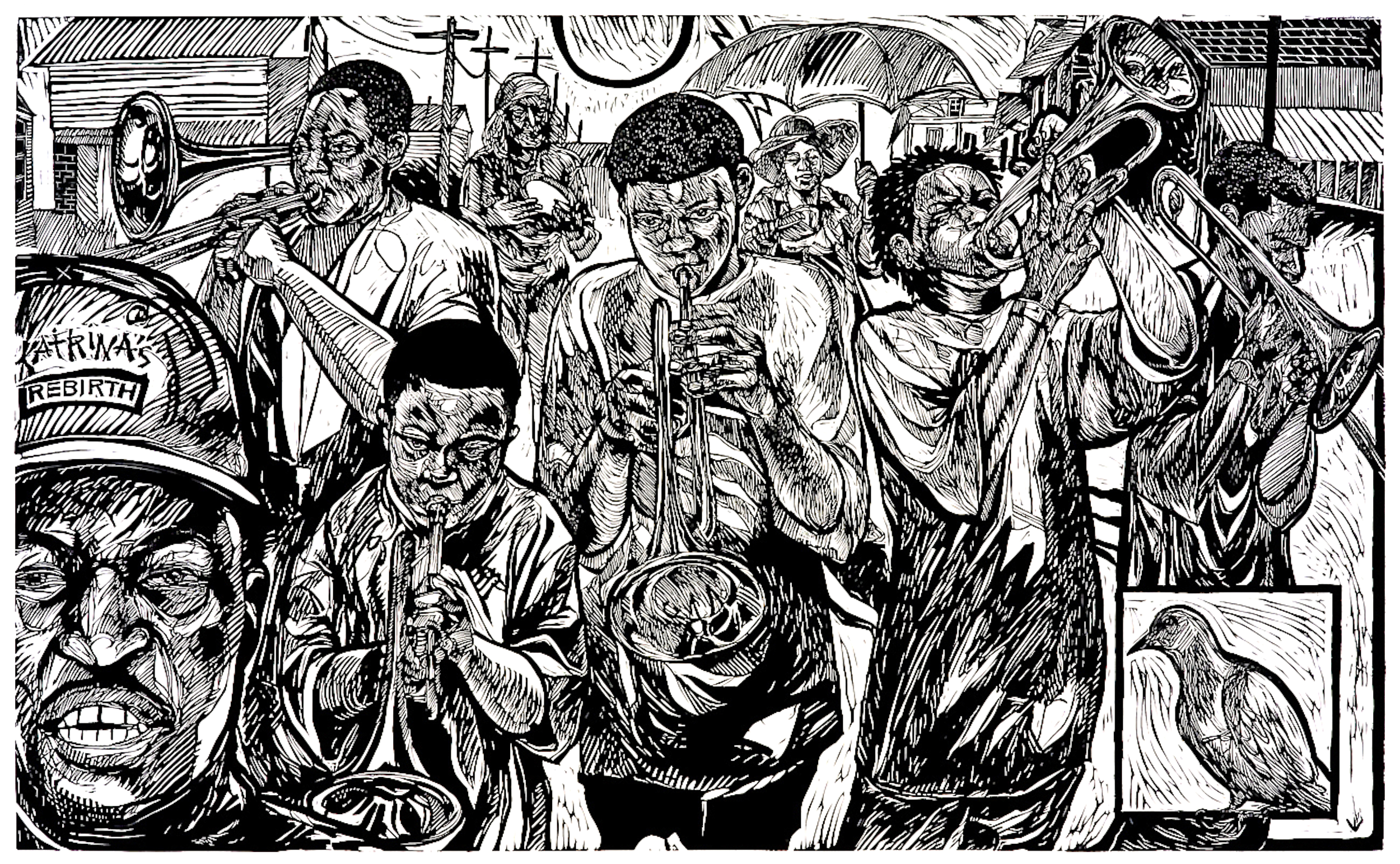

The funeral rites and parades of New Orleans actively seek to work against this silencing. Grief is externalized through the dirge, “a mournful song or poem,” and the dead are lamented and remembered. In Requiem for Brother John and Second Line: Rebirth, Steve Prince illustrates how mourners make sound, trumpets, as vehicles of grief and celebration, becoming loudspeakers, their soundwaves radiating like sunrays, as if the trumpeters are God’s angels ushering the dead into the afterlife, with electric poles that echo the cross in the background. Thus, the line itself can also be a visceral, physical form, a communal articulation and expression. Our discussion of the difference between being “on line” and “in line” highlights the implication of something perhaps more communal or unifying—to be “in formation” with one’s neighbor, to be deliberately unified and collectively a force that must be reckoned.

Requiem for Brother John

Second Line: Rebirth

Urban Garden was a mural or panorama that encouraged and necessitated the viewer’s active participation in movement to see every part of the piece. As such, the piece, too, relied on unity in its collaborative nature, not just in the process of creation, but in its continued work, the unveiling of sustained injustices and potentialities of growth in society. The viewer’s active gaze of seeing and engaging becomes a metaphor for effective action.

Our movement through the space of Prince’s work was also echoed in our movement of the classroom during Dr. Mark Broomfield’s dance lecture/exercise and our performance of the Clay Experiment, which recalled passages in Walking Raddy regarding the Baby Dolls and the gaze and visibility; the entitlement to, and assumption of, accessibility, of black women’s bodies; and the politics of space that controlled their movement and agency. In my last blog post, I wrote about how the segregated geography of Jim Crow New Orleans was an even more hostile place for black women because of their triple consciousness and how they subverted the fantasies, the gaze, and definitions others imposed on them to redefine themselves, their expression, and the space they occupied. In a sense, DuBois’ “veil,” a barrier of race, manifested in the Baby Dolls as a physical veiling, wearing masks and costumes and assuming performative identities. The Baby Dolls also threw back the veil, demonstrating their agency inherent in choosing what and how to unveil. They render themselves “public women” in choosing to be visible but remain “inaccessible,” delineating their own parameters of pleasure.

from Prince’s lecture, Kitchen Talk

Poetry and visual art both sustain memory. The interdisciplinary nature of this course and its interdisciplinary languages have widened my range of seeing and grappling, from learning how to analyze visual art to discussing history, dance, philosophy. In my recent serendipitous encounter with Ross Gay’s poem, “A Small Needful Fact,” I saw echoes of Steve Prince’s work. My reading of the poem became layered with Prince’s grapplings in Urban Garden, and I was able to create a conversation between the two pieces, although unintended by either party. In the poem the speaker imagines Eric Garner and the life-giving gardening in which he may have participated, having “worked / for some time for the Parks and Rec. / Horticultural Department.” During his lecture, Kitchen Talk, here at SUNY Geneseo, Prince explained the instrumental role hands—figured largely on both men and women figures in his work—of nurturing and sustaining life, stories, and traditions. Gay also emphasizes Garner’s life-giving, “very large hands” gently tending to the earth, “making it easier / for us to breathe,” in contrast to the police’s violent, life-threatening chokehold, making each breath for Garner a struggle until the last. In this way, poetry is similar to visual art in its investment in, and urging of, seeing, of bearing witness, and its potential to effect change. Even if that change is internal, to bring something into another’s consciousness is powerful because our thoughts can become our actions.