The course epigraph is quite powerful because it seems to be asking us, humanity, to think about issues that haunt our society. Since the beginning of our nation’s history, the injustices that have been weaponized against minority groups is unsettling. However, the courage of so many people to fight oppression is grounded in the fact that they did notice the ugly society around them. It’s more than just being aware of issues, anyone can see with their eyes. The challenge for us is to help others notice.

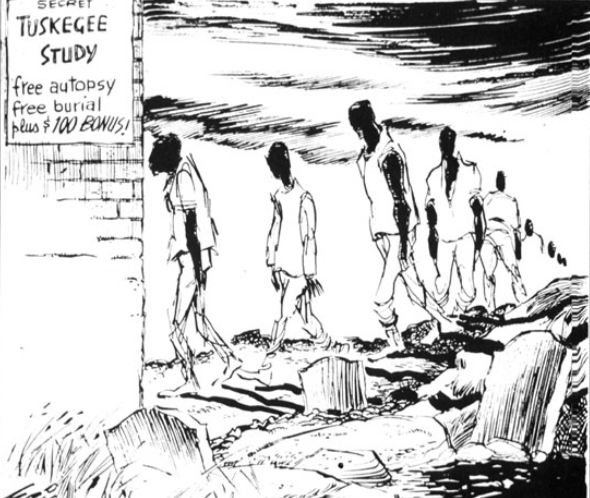

Most Americans have a decent knowledge of social injustices that African-Americans have faced since the first perilous journey of the transatlantic slave trade. Even today, unnerving videos of police brutality glares at us through iPhone screens. Prior to this class, I had a knowledge of African American history that was good…or so I thought. After reading Harriet Washington’s Medical Apartheid, I realized that I had only just begun to notice the much darker truth about Black suffering in American history. Like the construction workers at the Medical College of Georgia, who discovered nearly ten thousand bones of former patients, I have just begun to discover the chilling bones of our inherently racist medical world. Like it or not, it is our job to notice the history of African-American medical treatment and (hopefully) encourage others to notice.

Standards for what is considered racist have changed considerably over the years. Many doctors of the past believed that skin color was an indication of inferiority. They didn’t think twice about the humiliation of public display and invasion of privacy that allowed for medical dissection. Famed psychiatrist, Dr. Benjamin Rush, is known for his belief in “Negritude.” This held that black skin was a form of leprosy. Unlike the other doctors in Medical Apartheid, Washington asserts that his intentions were not racist. In fact, he was an active player in the abolition movement. His goal was to “cure” supposed diseases that made one’s skin color dark. By providing Black people with a treatment that lightens their complexion, then racism would no longer be an issue. Although Rush’s patients may not have consented to treatment and his approach still seems problematic, there was a legitimate effort to look at racism through a much different lens than others in his society.

This idea of separate black physiology was believed by scientists or doctors during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Granted, their views on race are much different than ours, but it was a step in the right direction. Another key player in helping society to notice racism was abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He spoke on the issue of scientists using unattractive Black people to compare against attractive White individuals. Beauty is a highly subjective term but Douglass was most likely using conventional beauty as a standard measurement. He drives this point home by claiming, “The importance of this criticism may not be apparent to all-to the black man it is very apparent.” (94) This quote shows that digging into social issues is an arduous task, but one that affects the lives of so many. Minority groups face oppression every day, so these issues are just a fact of life to them. When something becomes so commonplace, however, the necessary change is often neglected.

Realizing that we have a conscious effort to be (or not to be) accepting of racial differences is something that all Americans must come to terms with. Simply knowing isn’t enough. The insight gained from various stories of African-American allows us to spread it into the majority. A “silent majority” is not nearly as disturbing as a blind majority. Anyone can speak what’s on their minds, but not all can observe the long-lasting effects. As the struggle for equality raged on through the years, the few that helped others to notice should be recognized. The single-story of an oppressive master takes up too much room on the stage while the valiant efforts of the few are shoved backstage. Maybe one of us can take the center stage someday and help others to notice what we notice.