As a takeaway from this course, and in deep analysis of the literature, I am left with one vital reflection point that I will carry with me even as this course comes to its conclusion: How essential of a role should the different lenses of consent play in my own decision-making process for myself and others?

Throughout the course of the semester I have gradually built upon and reflected on my already existing thoughts of this courses central theme of consent. In studying works such as Percival Everett’s “Zulus”, Octavia Butler’s “Clay’s Ark”, and Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”, I was able to react to each of the authors takes on consent, communicated through the adversities faced by their main characters. Although the stories and each character might have been infinitely different at first glance, looking deeper, the works thematically shared the intention to inspire deep reflection on our society by carrying us through extreme scenarios of violation of consent in fabricated dystopian futures. Through the authors perspectives on consent within our society, they successfully created a plane of self-reflection and shock to their readers. In this plane, I was left questioning my own decision-process, and how each choice has consequences reaching far beyond myself. Thus, through their characters, the authors demanded a new level of self-awareness and change from their audiences, as to prevent any timeline similar to their own visions of a dystopian atrocity.

In analysis of each literary work, it became clear to me that the concept of consent should be an essential part of any decision-making process. In my eighth and ninth blog posts, both titled “The Power of a Decision: What motivates your choices?”, I was able to successfully unpack each of the authors’ goals in expression of their characters strife. Most notably in “Zulus” when Alice Achitophel and Kevin Peters decide just the two of them, to end all human life on earth. What gave them the right as only two people to make a decision for an entire planet? This question was applied again in “Clay’s Ark”, when Blake decided to escape the farm community, and as a consequence spread the “organism” thus threatening a world epidemic. In studying these drastic decisions, it invoked a conversation as to whether or not these acts where consensual or not. In my opinion, each of these decisions were an intense violation of consent as the characters failed to inform others or even consider other individual’s opinions on the matters at hand. Rather, in their positions of power, they made decisions that would affect numerous individuals without consulting any of them. Although these dystopian stories may seem entirely intangible, the ideas that they express are not entirely foreign to our own society. Whether in a position of power as a doctor, politician, professor, etc., these same ideologies that these authors share still apply. Consent by one for a decision that involves the lives of many is wrong. In conclusion, it is essential that when making decisions, we consider all perspectives and individuals involved, because if we don’t it is a violation of their consent.

Bouncing off of the idea that we must consider the perspectives of all, we come across the chronic issue of viewing other opinions as more important than others. Racism, prejudice, and discrimination are atrocious elements that have plagued our society throughout history. Tapping into this pain and violation of individuals, the authors of each of these literary works expressed that the dehumanization of those who are perceived as different is an intense violation of that individuals or groups consent. Through characters such as Alice Achitophel, and Whitehead’s take on the “skels” as told through his character Mark Spitz, the reader is able to visualize this prejudice in a new light. For example, Alice Achitophel is consistently criticized based on her weight, and outcasted from society. As a consequence of this alienation, Alice fails to be sterilized like all other women, and as a result becomes pregnant. Following Alice through her journey to escape the city and reach a “rebel-base”, we are continuously exposed to the crude and inhumane treatment that Alice receives due to these differences. Whether being ridiculed and aggressively assessed by doctors, or having her entire body be put on display in a glass case, Alice is non-consensually violated throughout the course of the novel. Analyzing Everett’s purpose for Alice Achitophel, it became clear to me that she was a representation of how we treat those who are perceived as different in society. In this reflection, Everett’s message comes at a shock that makes you rethink how you view consent both physically and socially. Alice is both physically and socially abused by her peers. With this malice you are left asking: What gave them the right? And what decisions led up to Alice being treated the way she was? I began to explore these questions in my final blog post titled “The Concept of Consent Analyzed through the Female Character Alice Achitophel”. In questioning the novel, it became apparent that the real-life applications of Everett’s warnings are both tangible and shocking.

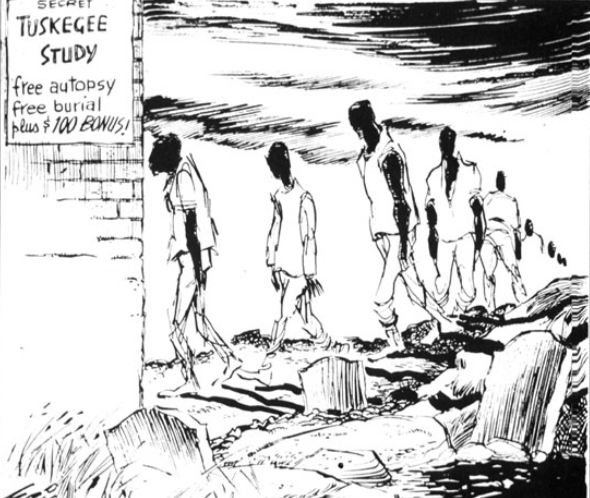

These applications are exceptionally evident in the medical field. In Harriet Washington’s “Medical Apartheid” she exposes multiple doctors who abused their power and status as physicians to non-consensually experiment on individuals who they viewed as less than. Whether African American prisoners, women, or etc., the nefarious actions of these doctors remained centralized on one excuse, they failed to acknowledge medical subjects as people worthy of receiving consent, or basic human rights in some drastic cases. In my eighth blog post, I analyze the horrific studies of Dr. Albert M. Kligman, who performed experiments on the African American prisoners of Holmesburg prison as to gain better knowledge in the field of dermatology. Zoning in specifically on Dr. Kligman, it became clear that often individuals put in positions of power, abuse this power, using others to better themselves no matter what cost to those individuals being used. In this case it was Kligman’s patients and experimental subjects who were being used. In the end, what does this say about our society? Reflecting on the literature, it becomes even clearer that we need to change this pattern of oppressive and selfish behavior in all regards and walks of life.

Delving into another real-life application, we can look closely at the NYC African Burial Grounds, and how they most likely inspired Colson Whitehead in his process of writing “Zone One”. The setting of Whitehead’s novel takes place in a post-apocalyptic setting of lower-Manhattan, ironically also where the burial grounds are located. The novel is based around a zombie-apocalypse, the characters referring to the dead as “skels”. However, unique to all the other characters, Mark Spitz is able to personify the dead, giving them stories and identities. Rather than just viewing them as less than human, Spitz views the skels as worthy of respect and a story. As a reader you are left questioning how can we possibly connect this to a palpable real-life scenario? Rather than focusing on the fact that the skels are quite literally zombies, if you look at the perspective of the skels just being individuals who have been dehumanized, the bigger picture becomes much more apparent. Thus, Whitehead’s purpose for his work becomes clearer. In my sixth blog post, “The Injustice of Dehumanization of Those Who are Different – Told through the Lense of Colson Whitehead’s Zone One”, I came to the conclusion that Whitehead’s goal was to make us question our own perceptions of individuals. In this contemplation, I was able to come to the fact that all are worthy of identity and rights in both life and death; thus, this historical pattern of disregarding human-lives needs to come to an end.

Circling back to decision-making, I was able to channel each of these authors works in order to improve my own thought process and reflect on the weight that consent should have on this process. Studying “Zulus” it became clear to me that we should all be more socially aware of our actions, as to prevent characters such as Alice Achitophel’s fate. In my tenth blog post, I state: “What gives someone the right to tell you that how you look and who you are is not okay?”. This question is carried from “Zulus” into “Zone One” as we reflect on Whitehead’s purpose to personify the skels, making a statement about how in history we have repeatedly given individuals no rights in death. This history is portrayed in the African Burial grounds of lower Manhattan, where the bodies of numerous African Americans were found completely unidentified with unmarked graves; thus, given no voice in life or death. A nonconsensual act that reaches far beyond just communication. This type of violation is again portrayed in “Clay’s Ark” when Blake shows zero regard for the consequences of his own actions, allowing the spread of a deadly alien organism worldwide, just so he could do what he desired as a single individual. All of these actions began with a decision. A decision that lacked inclusion of different perspectives, or regard for the lives of others. Whether deciding to end all human life as only two people (Alice Achitophel and Kevin Peters), potentially spreading a deadly organism (Blake), or viewing those who are dead as less than human (characters of “Zone One”), the violation remains the same: those who were not included in a decision but are deeply affected by it are robbed of consent at all angles.

So, in final reflection, for myself, and for the readers, I ask: How will you change your decision-making process after studying the messages of Everett, Whitehead, and Butler? And how can we improve our society by establishing that all are worthy of a voice and value in decisions that affect them?