The Water Cure by Percival Everett centralizes on Ishmael Kidder’s experience after his young daughter Lane was raped and murdered. The Water Cure has an extremely unique structure and style. Some sections are composed of a traditional narrative form. Other sections are not written in English or are misspelled. Some are riddles or drawings, and there are countless other forms. The Water Cure was introduced to our class as a book of “may or may not”s which prompted an investigative journey as I waded through the structure, style, and story. For me, the prompt had boiled down to ‘what is real in The Water Cure?’ and ‘what is not real in The Water Cure?’ In the back of my mind was the nagging idea of ‘what if both are true at the same time?’ I dismissed the idea when most of the secondary questions were based on assumptions that it was real. This reflection led me back to the excitement and overly complicated thought processes involved in ‘may or may not’— ‘real or unreal’—and ‘why not both?’

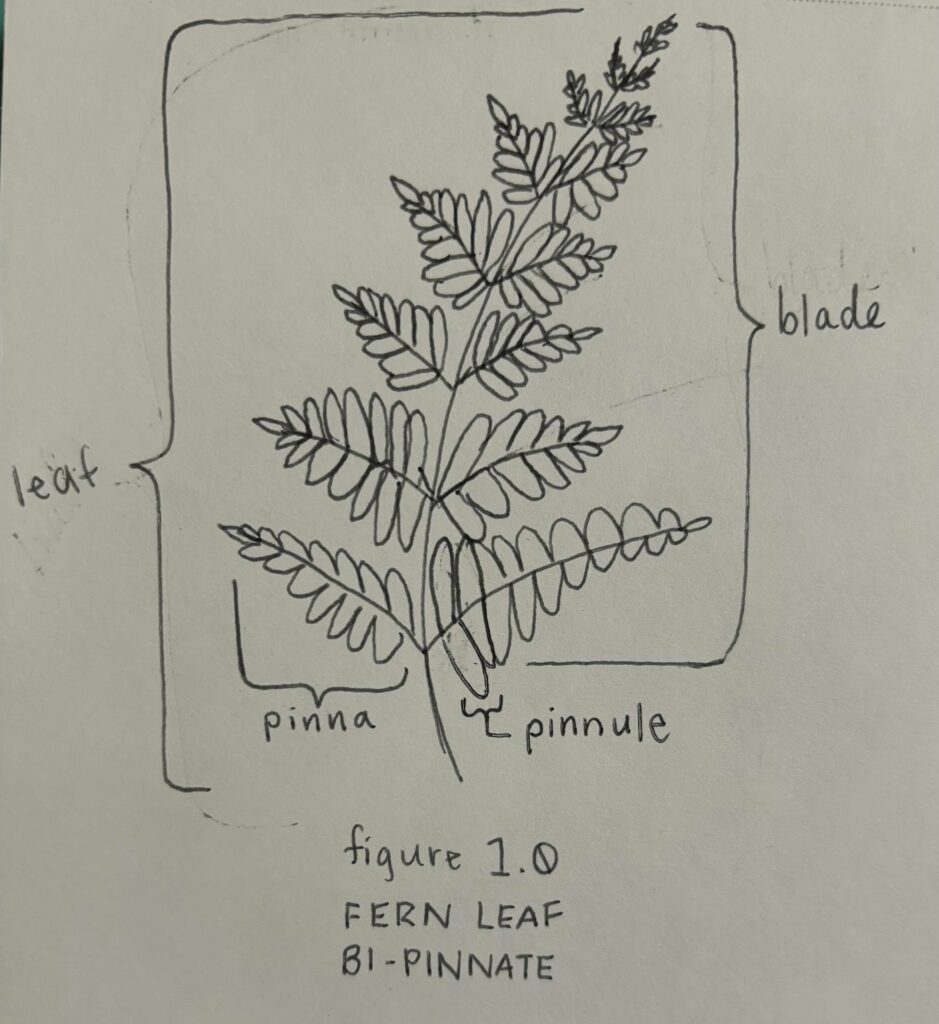

In African Fractals, the author, Ron Eglash, introduces the idea of “scaling shapes.” Eglash explains ‘scaling shapes’ as “similar patterns at different scales within the range under consideration.” (17-18) Essentially, the largest example of the pattern/shape will still look similar to the smallest version of the pattern/shape and vice versa. For example, consider a bi-pinnate fern leaf. The shape of the pattern repeats on different scales—the blade and the pinna (the first division). [fig. 1.0]

The blade and the pinna form the boundaries of the range, which Eglash references because there is no example of the pattern/seed shape that is larger than the blade and no example that is smaller than the pinna. [pattern/seed shape fig. 1.1]

While Eglash applies the mathematical concept of scaling shapes (an aspect of fractals) to African culture and life, scaling patterns can also be applied to literature. At the beginning of the semester, our class discussed the Western storyline pattern of ‘order –> disorder –> order restored’ [fig. 2.0].

On the largest scale, the story begins in a state of order (calm/stability), then something occurs that creates disorder (problem/chaos), and then (typically, the main character) seeks to restore order; once order is restored, the story ends. Within each of these overarching phases, there can be found ‘mini-stages’—smaller scales—of the overarching pattern [fig. 2.1].

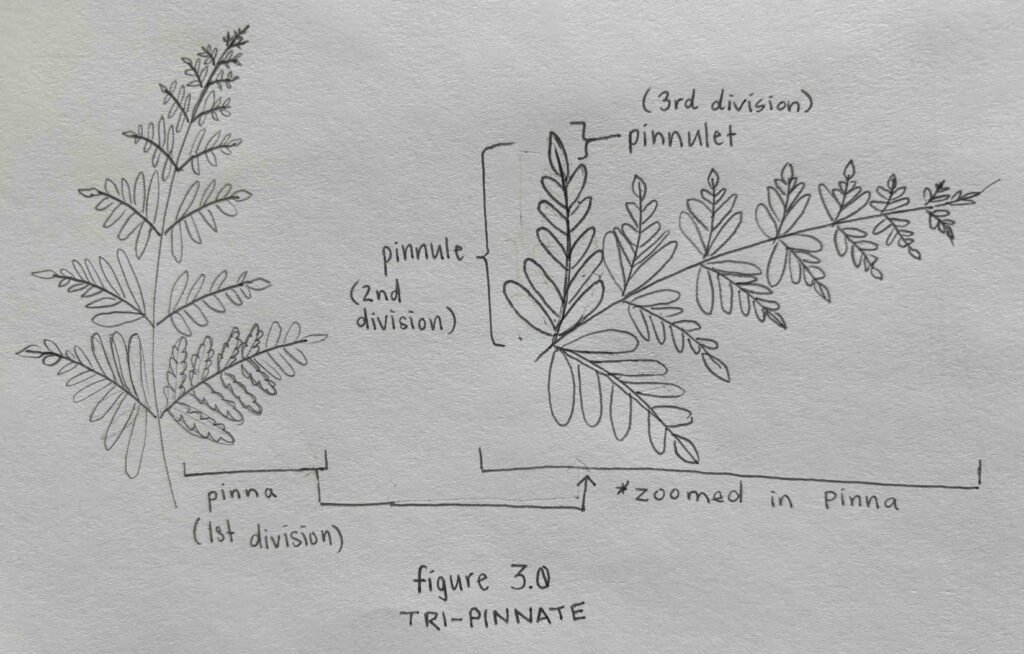

Hypothetically, this pattern could be nested infinitely, each recursive iteration being identical to the previous. Eglash calls this exact replication of pattern “exact similarity,” in which a replica of the whole pattern can be found within any smaller section of the whole (often referenced as scale invariance). (Eglash, 17) While exact similarity is mathematically and infinitely possible, in reality, as patterns repeat, they can become continually dissimilar with each subsequent iteration. Consider the fern again, but instead of a bipinnate—having two levels of division—it is a tripinnate (also called a 2-pinnate-pinnatifid)— having three levels of division [fig. 3.0].

A type of tripinnate fern is the Broad Buckler Fern (Dryopteris dilatata).

The shape of the blade and the pinna (the first division) look similar. The pinnulet (third division) looks a bit different from the first division. The pinnulets are blunter and rounder. With each subsequent division, the shape looks less and less like the original. Hypothetically, suppose there is a fern with a fourth, fifth, and sixth division, each iteration being proportionately wider and blunter than the previous division. Each division would look just a little bit different than the previous. Comparing the sixth division to the first division would look nothing alike, yet they originated from the same plant and form the range of the scale. In this case, self-similar scaling morphs into dissimilarity as the range continues until the finite boundaries.

Consider self-similarity (or dissimilarity) scaling in the context of The Water Cure, with the scaling factor being size and realness. ‘Realness’ in this context refers to how likely these aspects are occurring/ could occur in the physical world that Ishmael Kidder lives in, assuming he lives in a world similar/ identical to the actual world (the reader’s world); and thereby, how likely readers are to assume it is real (occurring in Ishmael’s physical world). Audrey Taylor and Stefan Ekman described this as the “primary world” in their article “A Practical Application of Critical World-Building.” They define a primary world as “a fictional version of the actual world, with only minimal differences, a ‘simulacrum’ of the actual world” (3).

Sections and details within The Water Cure vary in their perceived ‘realness.’ For example, one section that would be very ‘real’ is when Sally, Ishmael’s agent, goes over to his house, and they converse about how Ishmael won’t eat food from restaurants, and she asks him why there is a wad of duct tape on his mantel. The section is structured as dialogue and description. A scene identical to this could happen within the actual world and not be out of place. Thereby, this scene would quickly be presumed to be real.

Alternatively, a section that is not real (yet, complicatedly, exists within the book, so it is actually real within the audience’s reality) is when the text states:

The blue house on the corner is synonymous with the house on the corner is blue. She makes everything beautiful is not synonymous with everything beautiful she makes.

(Everett, 133)

While the statements are possible—there could be a blue house on the corner; there may exist a ‘she’ that makes everything beautiful—the section is not directly linked to the primary world. Like many sections in the text, it’s not exactly certain who is stating, thinking, or saying these statements of possibly fact, logic, and/or wordplay. While the previous scene occurred within the external primary world, there is no reason to assume that this second section occurs directly within the external primary world. Thereby, it is unreal. These two sections are extremes that help form the boundaries of the range from ‘real’ to ‘unreal.’

Traditionally, scale interacts with size. In the case of exact similarity, the shape/pattern remains the same while the size changes. The range is defined by size. The size of the division is directly linked to its sharpness/bluntness—largest/first division: sharpest; smallest/last division: bluntest—meanwhile, the range of the ferns scale becomes predominantly focused on sharpness/bluntness as the shapes become increasingly dissimilar with each division, but size still plays an important role. Consider the question, ‘is the fern sharp or blunt?’ The answer would vary based on scale—is it the blade, pinna, pinnule, or pinnulet? In The Water Cure, size and realness interact differently than in exact similarity. The size refers to the levels the text exists as—the book as a whole, a section, or a detail within a section. It is possible for different details, all within one section, to fall somewhere along the scale of ‘real’ and ‘unreal.’

These varying scales can lead to questions of ‘is this section real?’ even if it’s composed of details that the reader deems to be ‘real’ and details they consider to be ‘unreal.’ It is up to the reader to decide which details are real or unreal and how scaling aspects of realness interact and determine the overarching realness. The scaling patterns call into question the state of the book as a whole, ‘is the book real or unreal?’ much like the question of ‘is the fern sharp or blunt?’

As readers encounter The Water Cure, they determine their interpretations of what is real and what is not real. Each determination builds upon the last and shapes their understanding of the book. This process of definite determination, ‘either real or not real,’ is a common approach within our society. For instance, at a restaurant, if the waiter were to ask, “would you like salad or soup as your side,” the expectation is to choose only one option. This context refers to the exclusive form of the word ‘or.’ The exclusive ‘or’ means ‘one or the other, but not both.’

However, the inclusive form of the word ‘or’ refers to ‘one or the other or both.’ In formal Logic, a branch of philosophy, an ‘or’ statement (called a disjunction) utilizes the inclusive form of ‘or.’ I took a course on logic this semester that, upon reflection, I believe helped me to reconsider the question of ‘may or may not.’ Most everyday contexts in society (at least from my experience) reinforce the exclusive form of ‘or.’ When the class was prompted with a series of ‘may or may not,’ our minds were primed to assume the ‘or’ as exclusive. We can apply the inclusive ‘or’ to scenes within The Water Cure, meaning sections may be both real and unreal.

One scene that exists at values along the scale of ‘realness ‘ occurs in an early section of the book. In this section, Ishmael details that he has the man he kidnapped in his car and is having a conversation with “Thomas Jefferson’s ghost” who is in the passenger seat smoking a blunt (Everett, 34-35). The entire scene contains so many possible variations of realness and unrealness. [Fair Warning: it’s a bit messy and spiraling]

For instance, suppose it is Thomas Jefferson’s ghost: ghosts are a possibility/belief/superstition in the actual world. Deciding whether Thomas Jefferson’s ghost is ‘real’ in the book also entails deciding what is ‘real’ in the actual world. But suppose that, yes, ghosts are real in the actual world (real ghosts); therefore, they could appear as a real thing within the primary world (*real ghosts*). Then the question becomes, does Jefferson’s ghost adhere to the standards of a *real ghost*?

In the scene, Thomas Jefferson’s ghost is able to hold physical objects as he hands Ishmael the blunt. Does this conform to common standards of the abilities of a *real ghost* (in the primary world)? In other words, if a real ghost (in the actual world) isn’t able to hold physical objects, then is Thomas Jefferson’s ghost a *real ghost* (in the primary world), or is he a ghost that is real in The Water Cure, but simply not conform to the rules for real ghosts in the actual world. These questions of what constitutes a ‘real’ ghost can continue along this scale of ‘real’ ‘ghostliness.’

Simultaneously, there are other scales of realness when considering Thomas Jefferson’s ghost. Is this the real ghost of Thomas Jefferson? A scale of ‘real’ ‘Thomas Jefferson-ness.’ Does “Thomas Jefferson’s ghost” differ from the ‘ghost of Thomas Jefferson’ or from the alive Thomas Jefferson?

Speaking that this is Thomas Jefferson’s ghost and there is no difference between the previously mentioned variations. Then the question becomes, why would Thomas Jefferson’s ghost is having a conversation with Ishmael as he’s driving with a body in his trunk?

On the other hand, suppose ghosts are not real, so Ishmael may be hallucinating (or any of another multitude of explanations). If he were having a hallucination, the scene would be ‘real’ because hallucinations exist within the actual world. Simultaneously, if Ishmael is having a hallucination, what else is he hallucinating? Inevitably, this could disrupt the perceived ‘realness’ of the entire rest of the book.

The purpose of this example is to show how all of the real and unreal possibilities/variations makes determining the answer of ‘realness’ all the more complicated. These multiple interpretations of varying ‘realness’ can all exist at the same time. Often, the idea of an exclusive ‘or’ leads audiences to assume and assert one of these possibilities as definite truth, but it is possible for all scales of realness to exist at once. This relates to a principle of quantum mechanics, called superposition.

Quantum superposition refers to the nature of sub-atomic particles existing in more than one place or state at the same time. By being observed or measured, the particle’s position becomes finalized/determined. Superposition can be more easily understood utilizing the thought experiment called Schrödinger’s cat, which is used to describe the behavior of subatomic particles. The thought experiment proposes that a cat is placed in a box with a substance or device has a 50% likelihood of killing the cat in the next hour. After that hour, someone opens the box and sees that the cat is either alive or dead.

Schrödinger proposed that during the hour before the box is opened, the cat is simultaneously both alive and dead—it is in a state of superposition: being in more than one state or position at once. It is by the box being opened and someone looking inside that the state (or position) of the cat is forced to become either alive or dead. This is called the observer effect.

The observer effect is often referenced when considering the behavior of electrons, a subatomic particle that orbits the nucleus of an atom. Rather than the electron being in one particular place around the nucleus, the electron actually exists in multiple positions at once (in superposition), similar to how the cat was both alive and dead at the same time. If someone were to use a tool to measure the electron’s position, superposition ends (via wave function collapse), and the electron collapses to being in one place. It is by measuring (observing) the electron that the position of the electron collapses into one observed position within our reality at that moment.

The general concepts of the thought experiment can be applied to our reading of The Water Cure. The sections/aspects are in a state of superposition—simultaneously, real and not real. When we read (observe) The Water Cure we determine what aspects of the book are actually occurring in the external (‘real’) world of the primary world. The audience is the observer, like the person who opens the box to find the cat either alive or dead; the reader’s observation collapses the aspects of the book into one reality, either ‘real’ or ‘unreal,’ much like the cat becomes either alive or dead. The possibilities of realness and determination also interact with the scale of the book.

Considering “Thomas Jefferson’s ghost,” while it’s possible that this ghost could actually be his ghost or is merely a hallucination, it’s left up to interpretation. There are countless other sections and details that are also left up to readers’ judgment of what is and isn’t ‘real.’ (Not that this is necessarily a bad thing). By partaking in the act of reading, the audience (whether consciously or unconsciously) determines if a detail/section is real or unreal—what is happening in the primary world and what is not. Thomas Jefferson’s ghost becomes either real or unreal. Similar determinations are made as they continue reading. Determinations about details fall into determinations about sections, and sections into determinations of the book as a whole. Interpretation attempts to answer the ‘may or may not.’ I find myself still weary to choose a definite.

Applying quantum superposition to The Water Cure would suggest the possibility of an inclusive use of ‘or,’ meaning that instead of it being ‘may or may not,’ it’s possible that all aspects and sections ‘may and may not’ be co-occurring. In other words, before reading the book, these aspects and sections are each ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ at the same time. Every single scaling aspect, the scaling sections they compose, and the book itself as a scale may and may not be real, possibly, all at the same time. It is by reading the book and concluding that aspects are real or unreal that the audience exacts the observer effect and, by doing so, ends the superposition.

Applying the idea of quantum superposition to the practice of reading leads me to the hypothetical idea of (what I’m calling) ‘reading in superposition.’ Scientific experiments, like measuring the position of an electron, occur in the physical world, but reading and our interpretations while reading occur inside our minds. Physically, the particle is forced to collapse into one state when it is observed. For the sake of this argument, I’d like to entertain the idea that it’s possible to avoid collapse and maintain superposition while reading a text like The Water Cure.

To backtrack for a minute, in the physical world the particle collapses into one state because of the observer effect. Thereby, it is impossible to directly observe superposition in the physical world. But in our minds, multiple things can be true at once. For example, the idea ‘I could either go to class or sleep in.” Both paths can be imagined, and the repercussions of both actions can be imagined. Considering The Water Cure, it’s possible to imagine an aspect as both real and unreal, as well as the implications of both.

Reading The Water Cure in superposition would mean simultaneously interpreting (observing) every scaling aspect of The Water Cure as both real and unreal. As they continue reading, each subsequent aspect is considered real and unreal, branching off of the previous possibilities. This would create a nested system of possibilities. Reading in superposition only exists as an interesting idea because there are limitations—the human brain can only comprehend and focus on so many things simultaneously. Understanding gained from reading in superposition might allow an audience to understand many interpretations of the book, but to a degree, the amount of information and systems involved in this would be entirely tedious and repetitive. Meanwhile, understanding all the possibilities and variations of realness might not be all that valuable. For the sake of (even more) hypotheticals, reading the text continuously to attempt to absorb every possibility would not be reading superposition (and also be extremely tedious & repetitive).

In the physical world, the experiment cannot be rerun under the same exact conditions. The electron will be thrust back into a superposition state when it is no longer being observed. The conditions cannot be recreated; time cannot be rewound. Likewise, after we read a book for the first time, we cannot ever read it for the first time again. The experience and ideas we interpret during our first read will inevitably influence our experience reading it for a second time and the ideas we form during the second read. It will be a different experience occurring under different conditions. Which would mean it is not necessarily ‘reading in superposition.’ Additionally, the same book, especially The Water Cure, could be read repeatedly, each time striving to pick out another way of understanding the book or another branch of varying realness. The overly blatant question I propose at this point, which possibly serves to upend the entire journey of this piece, why would understanding every possible variation of realness or conceiving the superposition of a book even matter?

In short, it doesn’t matter. From a utilitarian standpoint, picking apart and comprehending every variation is essentially useless. Knit-picking to the thinnest branching details of a combination of realness will, at some point, yield no significant dissimilarity between the related interpretations. [Diagram] The Majority of the information absorbed, thus, becomes repetitive—like taking up space on a hard drive that could otherwise be used for valuable, more diverse information. In practice, most of the information derived from all those understandings would never have any use. Someone could write essays on a single source material for the rest of their life, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily useful or nuanced. While thought experiments and hypotheticals can be cool, it’s not always their actualization that matters; it’s the takeaways and new understandings gained that matter. The understandings gained from the application of superposition functions similarly.

Superposition can’t be observed, but the effects of superposition and how it governs the world can be observed. Superposition in reading is not possible (nor is it an actual term), but multiple different first interpretations of a book do exist at the same time because different people have different interpretations. That’s how people become aware of interpretations and understandings they have not previously or personally conceived. It’s a boring, basic given truth that is entirely understandable—human beings lead different lives, have different understandings, know different things, and thereby, form different interpretations. Different people assume different ‘real’s and different truths. This awareness of differences occurring simultaneously and all being true and real, relates back to superposition.

Awareness of superposition—the principle that something can exist in multiple states at once—is far more important than an imagined reading practice that attempts to observe a superposition. Mindfulness that multiple things may be/are true at the same time has impacts on multiple levels. When reading ‘realness’ in The Water Cure, superposition reminds us that just because we observe/assume an aspect to be ‘unreal’ does not mean it is the only possibility. One section may seem more real than another (such as the scene between Sally and Ishmael compared to the section about “the blue house”), but both exist on multiple values of realness. In other words, it is not ‘real or unreal,’ but both ‘real and unreal.’ The fern is both sharp and blunt. Likewise, our individual interpretations are not the only interpretations and are not the only ‘true’ interpretations.

The concept of superposition also has applications outside of quantum mechanics and reading The Water Cure. In real life, the awareness of more than one possibility being true lends itself to openness. Self-awareness that while I may hold one belief, someone else may hold another view; interpretation and truth are not universally definite. Superposition serves as a reminder that although I may observe/experience something and interpret/believe to be the sole answer (functioning off the ‘or’) there are multiple truths. My individual experiences—and those I can imagine akin to mine—are not the only experiences.

After completing this piece (I am, of course, hesitant to give it a definite name like essay or reflection), I’ve realized I may have absorbed more connections than I originally realized. Math and physics have applications and connections in cultural and literary worlds, but they also translate beyond the physical and into ways of thinking. Although something may first appear as strictly one seed shape or form, it exists in multiple dimensions and variations. Each is a valuable truth, but it is entirely impractical and impossible to know every single truth. I am also now realizing that The Water Cure was the perfect end to this semester as it has so many connections to topics and areas outside of itself.