By Abigail Kennedy

***

Warmed from the early sun, the sand pleasantly warms the soles of your feet as you walk. The sea, painted hues of yellow and pink, comes lapping at your ankles. Save for the call of some early-rising birds, the silence is only interrupted by the gentle splashes. A shining spiral pattern breaks up the sandy view below your heels as you stroll along the beach. Sand falls free as you raise it to your eyes. A conch shell rests in your palm: a spiraling piece of nature curated from fractals.

***

Fractals are mathematical shapes that endlessly repeat, often creating an end image the longer they repeat. Fractals are made up of seed shapes, the base image, or input for the fractal. This is what makes up the fractal with each iteration. In his book African Fractals Modern Computing and Indigenous Design, Ron Eglash defines fractals by explaining that “In iteration, there is only one transformation process, but each time the process creates an output, it uses this result as the input for the next iteration, as we’ve seen in generating fractals” (110). Iterations are the repetition of seed shapes, adding on to build through inputs and outputs. Overall, each component is needed to create the fractal. Much like fractals, the course ENGL 337, African-American Literature, has its recurring themes and concepts.

As the end of the semester approached, the class was tasked with reflecting upon our own growth and understanding of the course as a whole. From the very beginning of the semester, we looked at fractals and how they interacted, beginning with a read of African Fractals Modern Computing and Indigenous Design by Ron Eglash. Initially, I was curious to see how fractals interacted with African-American literature. I had worked briefly with fractals in my high school geometry class and had experienced them while reading Michael Criton’s novel Jurassic Park. Jurassic Park is a science fiction novel that features a cautionary tale about scientific advancements, more specifically genetic engineering. The story tells the creation and inevitable collapse of a park filled with scientifically engineered dinosaur clones. The dinosaurs escape their enclosures and chaos ensues. The book chapters are told in iterations of a fractal called the dragon curve, as shown below. Each iteration shows the park delving deeper and deeper into chaos and disrepair.

(Photo credit: TyrannasaurTJ)

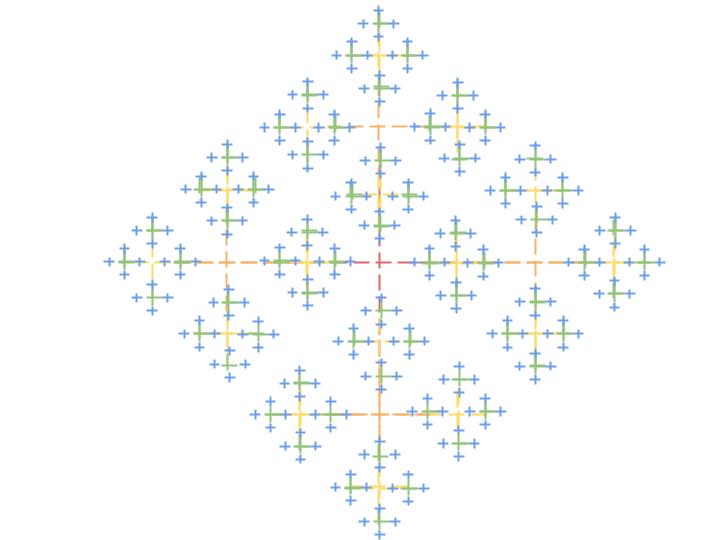

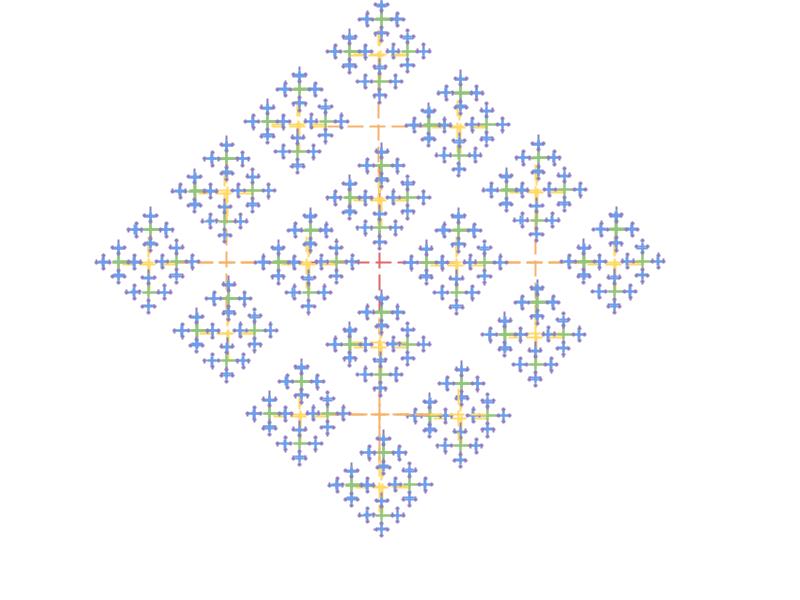

The novel’s approach to fractals inspired me to look at this course through the lens of a fractal shape. In this, I consider each module an iteration of the seed shape “thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING” or the course process. As each module looks at a different set of media and topics, it builds from the ones prior. The modules were all built with the process embedded into them, meaning that without the process the course likely would not work. Our instructor, Beth McCoy emphasized “thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING” ensuring that the class stayed on topic and properly gave every work its consideration. To properly analyze the course as a fractal design, I decided to create my own seed shape using Google Drawing and the draw line tool to develop with each module. The seed shape features four lines, each one representing one of the four processes.

***

Iteration 1:

“Course information, policies, and other important material to get started! You’ll return to this over and over throughout the semester”

As the first iteration of the course, this module establishes the seed shape and how it will be interacted with. I demonstrated the beginning of the seed shape, providing needed information on the course including, needed books, how we would be graded, and office hours. All of Beth’s policies are laid out for the class to see and access whenever applicable. The very first item is the course epigraphs and course descriptions. In this moment, the process is established, “In this particular 300-level course, we’ll place great emphasis on *process*: thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING as necessary preconditions for medical school, law school, activism, beING human.” In establishing this seed shape in the first iteration, students can consider the process and implement it moving forward. It is the start of a fractal-like course, showing itself in its first iteration.

Iteration 2:

“Here is where you can read Call and Response and The Water Cure”

The second iteration focuses more on providing information in the manner of resources. The books Call and Response and The Water Cure by Percival Everett are provided in .pdf files. Professor McCoy explains that “Within the last year, both Call and Response and Percival Everett’s The Water Cure have gone out of print. This creates a both/and: You both get access to these works for free, and you have to cross-check these .pdfs” (McCoy). In explaining this, we see the transparency policy established in the last iteration is built upon. This iteration allows students to begin the process, as without the resources, thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING would be rather difficult to achieve. This iteration shows the fractal’s growth, as well as the course’s.

Iteration 3:

“Key Concepts”

As the iteration that begins with the first week of classes, establishing a starting point while building off the first two iterations is key. The course structure is established here, as well as a reminder of one of the epigraphs stated in the first epigraph. This iteration builds off of the epigraphs, beginning the classwork involving African Fractals and Call and Response. Here we find the use of thinkING and considerING. The class begins to connect concepts of fractals to themes in African-American literature and repetition in the culture. However, we discuss the importance of not making immense generalizations, utilizing the reflectING part of the seed shape. Finally, we utilize conversING in the manner of class discussions. These can be as a whole, or in small groups, analyzing parts of the readings and how we interpret them. The seed shape repeats itself, adding more to the fractal shape.

Iteration 4:

“Noticing the Depths”

The fourth iteration features yet another course epigraph from the first iteration. Building off the last iteration, this module focuses on growth. As Professor McCoy notes, “This module enables you to apply and practice concepts from Module 3. In doing so, you may notice that things are more complicated than they may at first seem.” The focus seems to be on truly thinkING and considerING. However, a look at the notes from class on February 9th reveal another consideration of conversING. Without participation, conversations run dull and awkward. However, another consequence is the lack of true reflectING. If only one voice is heard, then the views are limited and biased. To work as a whole class is to truly interact with the process. The iteration can only show the addition of the seed shape with the proper conversation.

Iteration 5:

“Integrative Inquiry, Sustainability, and Collaboration”

An iteration focused on three concepts develops upon the works used in the previous iterations. In this module, work was done on the Collaborative Exercise, where we were grouped together to answer the prompt on sustainability and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. We were also encouraged to include poetry regarding sustainability and think back on the visit the class made to the college’s heating plant from the last iteration. A collaborative exercise demonstrates the process as it requires students to think thoughtfully about the prompt, reflect on how it all ties together, converse with one another in order to answer the question, and consider feedback from peers and each work individually. This iteration works to build off of the work done in previous iterations to create the newest addition of the seed shape.

Iteration 6:

“Criticism, Theory, and Poetry are the works of complicated human beings”

Once again, we begin the iteration with reminders of two epigraphs from the first iteration, demonstrating the repetition seen in fractals. The module worked with comparisons and both/and exercises. We looked for similarities and differences in works, and carefully navigated through opposing essays from Joyce A. Joyce and Henry Louis Gates. Emphasis on slowing down to truly work through the process was given. In slowing down, we were able to truly apply the process to the works, giving them the time they needed to truly find the things we liked and disliked and why. While thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING we were able to work through these concepts as well as get through Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia. While working through this work, we acknowledged that it was both racist and important, as Jefferson was a complex person. This reading was set to establish the beginnings of the next iteration, sewing seeds within the seed shape.

Iteration 7:

“Endings that aren’t endings”

This final iteration, appropriately titled “Endings that aren’t endings” begins with Percival Everett’s The Water Cure. Professor McCoy begins with the statement, “In this module, you’ll return all the way back to the very beginning of the course–including to “On Repetition in Black Culture” and to African Fractals–even as you read the semester’s final literary work: Percival Everett’s The Water Cure. We’ll talk about beginnings, middles, and endings. And you’ll liberate yourself from the class.” As the final iteration, it is imperative that considerations are made to the first one. As the class worked through the novel, encouragement was made to consider the past works, to reflect on what we thought and how interacting with the novel made us feel, to think beyond what was just on the page, and to converse with one another on our findings and interpretations. Without this process, navigating through the novel would have been a much different experience. Every experience we had before enabled us to interact with The Water Cure in a more careful and considerate method. As the course comes to a close, the seventh iteration shows the fractal we created.

***

As a class we discussed whether or not we thought ending the class with reading The Water Cure was appropriate. A majority argued that it was, deciding that every module before was established to prepare us for the novel. I could not agree more. Without our careful work with the process throughout this semester, navigating the novel truly would have been much different. Having the course focus on thinkING, conversING, considerING, reflectING, and using the process with every module, we were able to become comfortable with it. We could implement it without much issue. However, I must divulge a word we also worked with in conversation: apophenia. This is the habit of finding connections or patterns between unrelated or random things. Professor McCoy has worked with this word in both this course, and one I took with her prior based on Expulsion and the 2018 Housing Crisis. While I was able to find the connections between each module, and therefore apply them to the iteration concept, there is the risk that I am assigning meaning to something unintended. Regardless, I find that in my own reflection of the course the process has allowed me to find a deeper understanding of African-American literature and given me the opportunity to engage meaningfully with my peers.

Works Cited

Eglash, Ron. African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design, Rutgers University Press, 1999.

Everett, Percival. The Water Cure. Graywolf Press. 2007. Percival Everett, The Water Cure.

McCoy, Beth. ENGL-337-01: African-American Literature. 2023-2024