Recently, I had a conversation with a friend about being more conscious of how much space you take up, physically or metaphorically. We talked about it through the lens of leadership, and how a mark of maturity is being conscious of how much attention you are putting on yourself, or how much space you take up, and when to shift the attention to others, or when to share space with others. Continue reading “Taking Up Space (Physically & Metaphorically)”

The Haint and Childhood Trauma

In class last week, while we were discussing The Turner House, the topic of trauma was brought up. Assuming that the characters encountered no trauma as children made me think of the Xerox Seminar Series titled “Adverse Childhood Experiences.” Continue reading “The Haint and Childhood Trauma”

Mexico City and How Water Begets Poverty

The below post is based on the information from this article. All credit to Dr. Ryan Jones and his History of Modern Mexico course for leading me to this information. Continue reading “Mexico City and How Water Begets Poverty”

How Much Does Language Matter?

I have been thinking about what Dr. McCoy said on Monday about using ‘slave’ vs. ‘enslaved person’. This issue of language is something that has bothered me a lot in the past. Continue reading “How Much Does Language Matter?”

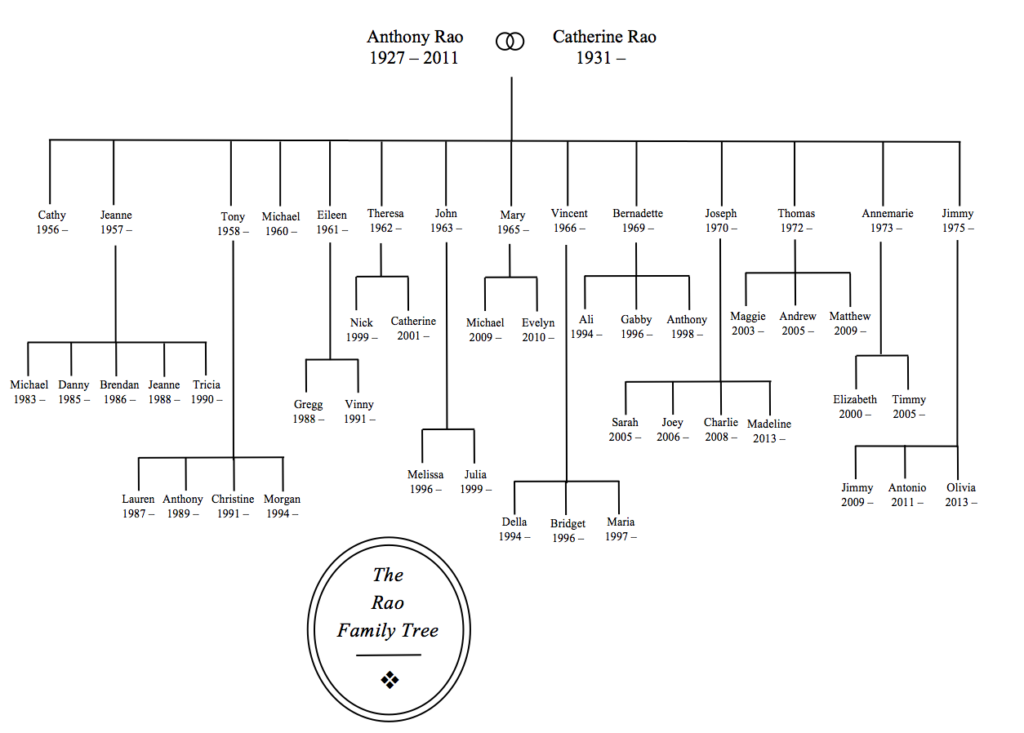

Big Family Trees

When we first started reading The Turner House I was immediately hit with a rather strong sense of déjà vu as I came across in the paratext the family tree that Angela Flournoy prefaced her novel with. I took note of the many branches extending from the Turner patriarch and matriarch and saw an immediate correlation to my own extended family. My dad is the seventh child out of fourteen and grew up in a household that was a little bit different from the typical household at the time comprised of two parents and three and a half children. I felt the desire to compose my own family tree for a visual representation of the similarities that I see my family to have with the Turner family. Viewing that family tree laid out with three generations of Turners really reminded me of my family and prompted me to give a closer look to the sibling relationships within my own family.

When we first started reading The Turner House I was immediately hit with a rather strong sense of déjà vu as I came across in the paratext the family tree that Angela Flournoy prefaced her novel with. I took note of the many branches extending from the Turner patriarch and matriarch and saw an immediate correlation to my own extended family. My dad is the seventh child out of fourteen and grew up in a household that was a little bit different from the typical household at the time comprised of two parents and three and a half children. I felt the desire to compose my own family tree for a visual representation of the similarities that I see my family to have with the Turner family. Viewing that family tree laid out with three generations of Turners really reminded me of my family and prompted me to give a closer look to the sibling relationships within my own family.

Children in Poverty Clip

We watched this clip in my EDUC class this semester and because of the course content and current political attempts to defund certain after school programs, I thought this would be good to share.

Gluttony and The Terror of the Great Outdoors in Lelah’s Eviction

As I traced Lelah’s story of eviction and homelessness throughout the five weeks of Spring 2008 in The Turner House, my mind kept returning to an excerpt we read in the beginning of class from Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. In it, Morrison attests that:

“Outdoors, we knew, was the real terror of life. The threat of being outsiders surface frequently in those days. Every possibility of excess was curtailed with it. […] There is a difference between being put out and being put outdoors. If you are put out, you go somewhere else; if you are put outdoors, there is no place to go.”

Morrison’s excerpt is particularly harrowing in light of the story of Lelah: who, after being evicted from her apartment, spends much of the novel building upon lies to hide her homelessness while squatting in the Turner house as a buffer to avoid the terror of being put outdoors. The part, however, of Morrison’s analysis that interested me most in connection to Lelah was her description of outdoors as a curtailing of excess. In The Turner House, Flournoy dedicates much of the first chapter novel to narrating Lelah’s humiliating and painful eviction, in which she has two hours to pack her belongings into her car under the watchful eye of two bailiffs. Flournoy writes, “Mostly, all Lelah did was put her hands on the things she owned, think about them for a second, and decide against carrying them to her Pontiac.” Ironically, rather than trying to cram as much of her possession as possible into her Pontiac, Lelah chooses to leave the bulk of her belongings behind. Flournoy clarifies that “Furniture was too bulk, food from the fridge would expire in her car, and the smaller things–a blender boxes of full costume jewelry, a toaster–felt too ridiculous to take along.” Here, the restriction Lelah places onto herself harkens back to Morrison’s intriguing observation that being “put outdoors” means to curtail every possibility of excess. Lelah’s possessions–the sum of years of accumulating “ridiculous,” but surely meaningful, artifacts–become reduced to triviality through the act of eviction.

The relationship between Lelah’s eviction and the curtailing of excess, of course, reminds me of a point made by Roach that we’ve returned to multiple times throughout the semester–his insight that “violence is the performance of waste.” It is not coincidental that when Lelah is evicted, the sum of her possessions that she can’t take in her Pontiac (her furniture and countless objects she trivializes as ridiculous, among others) will be disposed of in a dumpster. Her eviction, then, effectively performs waste: as the collected material value of the objects in her apartment aren’t going to be recycled or repurposed into further use, but are instead reduced to trash. The eviction also performs violence onto Lelah–a point that Morrison exemplifies in her excerpt exploring the terror and fear of being put outdoors. There’s a lot more to say on this subject, but for now, both Roach and Morrison have informed my own previous reading of Lelah’s eviction and prompted me to think about the ripple effect eviction causes in both paradoxically promoting violence and restricting the gluttony of material excess.

A House Analogy Related To The Turner House

While thinking about progression in The Turner House last class, I remembered an analogy that I had stumbled upon before even starting the class. I found this analogy in a horror game called “ANATOMY.” At $3, the game is a surprisingly eerie and tense interactive story, revolving around finding and listening to cassette tapes in an old and dimly lit low-fi house, which teach you about, as described by the indie developer Kitty Horrorshow, “the physiology of domestic architecture.”

Continue reading “A House Analogy Related To The Turner House”

Good Writing and Trust

As Dr. McCoy pointed out a couple classes ago, we all started to read The Turner House with expectations. For me, a lot of my expectations for the novel were framed by the fact that we’re reading this in a college course and plenty of news outlets had named it the best book of the year. However, pretty much all of my expectations were thwarted, and, sadly, not in a good way. Continue reading “Good Writing and Trust”

Recontextualizing Water And Cyclical Rebirth in T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland”

In class last Friday, we ended our discussion on the language of water metaphors in finance by looking at common symbolic associations of water in literature, including the use of water to evoke symbolism of purity, vitality and renewal. We then touched on texts that aim to recontextualize the symbolic association connecting “water” to “purity,” and I mentioned T.S. Eliot’s modernist poem “The Wasteland” as a central modernist poem that invokes water imagery to highlight the growing accumulation of decay and disintegration in Modernist Europe.

Eliot plays with water imagery throughout the poem, but his most telling use of water imagery occurs in Part III of the poem, ironically titled “The Fire Sermon.” According to the footnote for the phrase “Fire Sermon” in my copy of “The Wasteland,” “The Buddha preached the Fire Sermon against the fires of lust and other passions that destroy people and prevent their regeneration.” Here, the Bhudda’s cautions of excessive lust and passions that prevent “regeneration” serve as a stark foreshadowing of the remainder of the section, which explores devastation in modern London. Eliot suggests, then, that the West perpetuates a state of crisis in modernity, a commentary reinforced by his evocation of Eastern ideals pitted against Western gluttony.

Continue reading “Recontextualizing Water And Cyclical Rebirth in T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland””