Blog Post Written by:

Alexis Banaszak, Kazon Robinson, Madison Jackson, Mary Rutigliano, Joo Hee Park, Melisha-Li Gatlin, Devin Hogan, and Cindy Castillo

Sustainability is a definition that is not fully set in stone. In fact, the term sustainability has no self-sustained answer because of its wide and various meanings. Every person interprets sustainability differently. For some, sustainability is a matter of maintaining something to a certain level. For others, sustainability is focused on the environment and fighting for conservation matters. Generally speaking, sustainability is structured by three pillars: environmental, economical, and social and that we need all three pillars to aim for sustainability. Our group first searched the definition of sustainability and decided the definition with the best fit is from the website YadaDrop. The website defines social sustainability as “an ethical responsibility to do something about human inequality, social injustice, and poverty.” This definition strongly resembles Prince’s compositions and content. Over the entire semester our class has been filled with intellectual curiosity about what Prince tries to unpack in his work. From the pieces we have examined in class, our group agreed that there is a both/and with simplicity on the surface and multiple meanings upon analyzation.

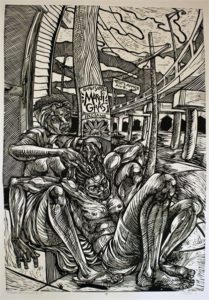

Judges: Delilah Didn’t Do It by Steve Prince

One composition that our group believed addresses the both/and is Prince’s Judges: Delilah Didn’t Do It, which discusses the three pillars of sustainability in both the work itself and the stories he tells about it. The print depicts two people in the left forefront sitting on a stoop, a man reclined in a woman’s legs while she braids his hair. Bisecting the print at the near center is a telephone pole with a Mardi Gras Indians poster. The sky is cloudy. Swooping down from the right corner is a highway raised above the ground that goes into the background and goes out of sight at the center of the print.

Prince has remarked that there used to be oak trees all along Claiborne Avenue. When the I-10 invaded the community, the oak trees were removed and relocated (serious h/t to the Congress for New Urbanism, which has a encompassing, not too long article about the I-10 in New Orleans) and 500 homes were razed. The community lost those trees and traffic increased in the area. In a study published in March 2019, researchers shared results that depicted racial and ethnic disparities in pollution consumption and creation. They found that white Americans consume less air pollution, but the rate of practices that lead to pollution are greater than those Black and Latinx communities.

Prince’s work may be seen to raise questions of what practices or power structures are preserved or perpetuated, what practices and truths are erased or submerged (literally and figuratively—e.g. Prince spoke about how he lost childhood photos from the hurricane, families lost their buried loved ones). Prince sustains multiple traditions through his art: heavy layering of symbols, texts, and stories in his work are rooted in his religious background and oral tradition of storytelling. In borrowing and revising preceding artwork, Steve interweaves personal, political, contemporary, and historical stories into conversation.

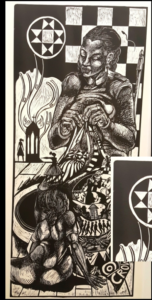

Sow by Steve Prince

Prince is an active voice in his work as well. Prince says, “I speak, too, and I’m a part of the art.” His art hopes to effect change in its immediacy and visibility of such social, economic, political injustices. In his involvement in community-focused art, specifically Urban Garden here at SUNY Geneseo, Prince’s goal was to engage students in an active “improvisational mural” and collaborative space, a “metaphorical garden” representing what is sustaining the soil and what needs to be sustained, as well as a “futuristic image of who we can be” portraying goals of sustainability such as equality or better standards of life for all. In his recent lecture, “Kitchen Talk,” Prince shared his work, Sow, the first piece of the kitchen series, which centers the kitchen, a space that is one of the most important rooms in a house and where so many stories are told and untold. Both Prince’s mother and sister were, or are, quilters; the layered meaning of “sow,” in one part recalling to the labor of enslaved people, exemplifies the intricate interweaving of stories and symbols that coheres as one patchwork, each piece a discarded story re-sown, to be disseminated to the world. The figure with multiple legs underskirt speaks to both the personal struggle, though not an isolated plight, of Prince’s grandmother hiding her children into the train and the collective struggles, alluded to, for example, by the symbols alluding the church bombings.

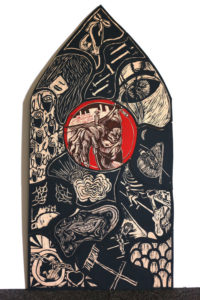

Old Lady in the Upper Room by Steve Prince

Prince, through his artwork and projects, emphasizes and incorporates all three pillars of sustainability and creates a basis for a commentary about human experiences. Projects Old Lady in the Upper Room–the piece used for a public reading event to vocally apologize to Natives– and Urban Station all display this observation by actively embedding cues hinting to social disparities, reform and “spiritual cleansing.” Upon first analyzing, we did not know how to interpret the piece. At first, Alexis thought that the lady was reaching towards what was in one of the horsemen’s hand. Melisha then suggested that perhaps she was reaching for the little girl on the other side of the room. Then, Devin and Kazon were going back and forth on the idea that the little girl and the older woman could be the same person, but in a different time. After that was out in the open, Alexis pointed out that maybe Prince uses the lighting scheme of dark versus light to contrast this. After further discussion, our group related it to sustainability, specifically to the social pillar. One of the horsemen is holding a watch which we interpreted as representing life and death. We then started thinkING about how when we were younger, we did not know much about how our actions can impact both our environment and the people around us. As we grow older, we start to realize how much our actions can directly impact society (negatively or positively) which forces us to start taking action.

Sojourn Arts: 12. Jesus Dies on the Cross by Steve Prince

In addition, we also discussed Urban Stations which addresses the social pillar. At first, our group noticed how Jesus’ crucifixion is being portrayed with harsh judgment. The people who congregate in the church have a mission for people to solve injustices through the teachings through the eyes of Jesus. However, despite the good intentions of this call to action, it does not solve anything in our society. For example, people who are very religious believe that they are helping society and are doing God’s work by killing the “sinful.” Although the person in which they want to kill may have “sinned” it still does not address the bigger social issues such as the injustices in the criminal system persecuting the wrongfully accused. Therefore Urban Stations is an example of how people are trying to address the social pillar of sustainability; however, it is not always successful.

As we consider the sustainabilities of our communities, the structures we live in, and our impacts to others, we’re faced with what may seem to be a dichotomy. Contemporary sustainability movements and even activities on campus can easily sit themselves in trying to change individuals’ actions, rather than pointing to systems that create unsustainable Prince invites us to partake in a both/and approach to the pillars of sustainability, and especially in Urban Stations, his collaboration with the community at Sojourn Arts. The 12 pieces of the work that depict the Stations of the Cross. His artist’s statement says, “He [Jesus] rose again as a fulfillment of the scripture and as evidence that we may go through trials individually and collectively…” Sustainability requires us to place our feet in separate camps. The way we live and and participate in systems like racism and the consumption of fossil fuels is unsustainable. We simply cannot continue in the way we’ve been practicing, so we need to create new pathways, new structures. Yet at the same time, people live by fossil fuels, un-renewable energy, or are victimized by racist criminal justice systems. We need to attend to these new realities as we mitigate the one we are currently in. W.E.B. Du Bois engages with this very idea in his chapter, On the Meaning of Progress. He writes about the farmworker families in his school district’s need to take out their children to work the land. Du Bois, had other hopes for the way schooling was valorized, “When the Lawrences stopped, I knew that the doubts of the old folks about book-learning had conquered again, and so, toiling up the hill, and getting as far into the cabin as possible, I put Cicero ‘pro Archia Poeta’ into the simplest English with local applications, and usually convinced them-for a week or so.” Here Du Bois uses Cicero’s works to show the community the value and the necessity of preparing for a different world. In Urban Stations, Prince shows the importance of working within a system to ease pain and aid those targeted and victimized, while calling on a larger community to create a world where such suffering doesn’t happen.

Sustainability is a complex issue, not isolated to environmental crises but deeply intertwined with, and implicated by, social and economic problems as well, such as better standards of living for all. Sustainability includes our responsibility as humans not just to the world in which we live and those who will inhabit it but also to one another, now. In contemplating the environmental questions of sustainability of how we may “live in harmony with the natural world around us,” we must also invest ourselves in the question of how we may live in harmony with, serve, and protect our neighbors, as Prince urges, and allocate resources to all, especially the underserved, recognizing the deeply entrenched, imbalanced power structures at this particular juncture. Thus, sustainability is about sustaining voices and carving out inclusive spaces, preservation and survival.

So when we are discussing social issues, we are left with a particular question that either pushes you to action or inaction. The biggest question asked then is: “So What? Who Cares? Is it a big deal?” For some, this question is daunting because it reminds groups or individual people that the experience or problem they face are not universal and cannot be perceived in such a way. In the context of the social pillar questions like, “Who cares about equitable wages” or “What’s the big deal with conservation?” remind us that our problems are not others problems. However this type of thinking is dangerous when we look at it in application to artists like Steve Prince or writers like Du Bois.

Steve Prince is constantly discussing about issues surrounding the black experience and furthermore about the social aspect of the pillar. For example, his piece, Old Lady in the Upper Room can be a commentary on intergenerational knowledge. Intergenerational knowledge, holds great value because it provides frameworks to solutions or ways to go about solving solutions. From making policy driven decisions to everyday actions our ability to make choices is dependent on that knowledge being carried between generations. Therefore, Steve Prince is able to call into question the danger of intergenerational loss by showing the four horsemen. Specifically the four horsemen represent deadliness or danger and for the people dealing with the experiences they may be lost to “time”.

In the context of the social pilar, social issues do not need to matter to anyone. For example, when issues of race are brought up, people can and actively choose to deflect these issues. Robin DeAngelo, writer of White Fragility, discusses how concepts like niceness and closeness convey not being racist. This type of thinking amongst other forms of deflections is not explicitly asking “So what” but the implication still exists. Instead of learning of tools or ways to discuss race, people may assume that some level of niceness is what is needed to combat racism. For instance, in Du Bois’ novel, Souls of Black Folk, he discusses race and racialized issues on the black experience. For example his famous quote, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” When Du Bois writes this he means that although slaves were freed, black people in society have to face discrimination based on the prejudices of pigmentation. Therefore, when people ask “so what?” they should know and recognize that discrimination still occurs in modern day America. So, we as members of society should call to action and make a change instead of ignoring America’s racial problems.

What are we doing in terms of addressing sustainability? Are we sustaining conversation on tough topics like race, sexuality, gender, or immigration? Are we challenging ideologies or supporting them? Are we supporting certain biases or preconceived notions over others? The more questions we ask about this, the more Steve Prince’s work becomes relevant to the conversation on sustainability. Steve Prince is both putting in the work around sustainability but never removes himself from being in the process of improvement. Therefore when people ask “so what”, respond with another question: “What have you done? And what are you going to do?” From there we can use our own skills, whether it is in the arts or in the sciences to challenge the social, environmental, or economic pillars that block all of us from reaching our fullest potential.