The multitude of stories contained within my experience with this semester can hardly be reduced to the scope of a singular blog post. From the conceptual seed shapes planted at the beginning of the semester to their seemingly endless strings of iterations and reiterations, the full sprawl of insight I have gained throughout my time in this course can be overwhelming to mentally parse. Taking stock of all I have learned, it makes me wonder how much a survey course such as this one can truly give an accurate and complete picture of the literary tradition which it covers. I had never even heard of the majority of the authors and works we discussed and was largely unfamiliar with many of the core concepts, which seems to me now to be a failure of my education up to this point, but I recognize that these can still only portray one slice of the entire body of African American literature.

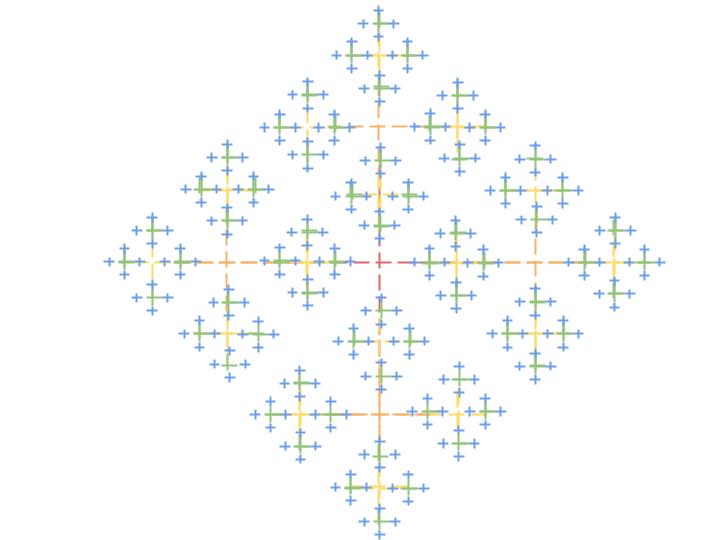

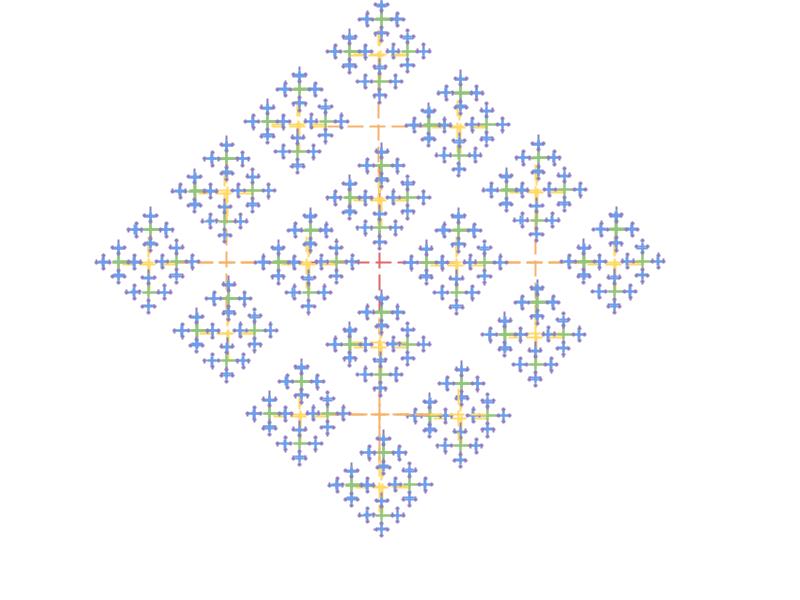

Unsure of where to take this strand of thought, I turned to the initial groundwork upon which we built our studies in this course. We started the semester by examining Ron Eglash’s African Fractals, which gives a mathematical overview of the principles of fractal geometry that lay at the core of traditional African design. Eglash goes over a few central mathematical concepts evident in various areas of African design, and connects them to the cultural ties related to these concepts: most significantly, the fractal principles of recursion, numeric systems, scaling, complexity, and infinity. The one of these that I feel is most pertinent to my experience with this course is scaling, for a variety of reasons that I hope to make clear.

Eglash identifies scaling geometry quite broadly as “mathematical practices in thinking about similarity at different sizes” (71). It may also be described as “irregular geometric structures whose shape seems to be self-similar regardless of the level of magnification at which it is viewed” (Fractal-Scaling Properties as Aesthetic Primitives in Vision and Touch | Global Philosophy). In my understanding of the term, I take scaling to mean the process of applying identical ideas at varying magnitudes, sometimes to a dramatic extent. Scaling in the mathematical sense has many practical applications, as shown by Eglash in the “cost-benefit analysis” of African wind-screens using scaling techniques (73), but the more abstract concept of scaling can be seen represented in storytelling models, and will serve as a framework for my own analysis of my time in this course.

For example, scaling is used as a primary thematic mode in Percival Everett’s The Water Cure. Graywolf Press, the novel’s publisher, describes the story as confronting “the dark legacy of the Bush years and the state of America today,” yet the narration almost never engages directly with the former president or his administration. Rather than undertake a face-value indictment of the Bush administration’s response to the September 11 terrorist attacks, Everett scales down the atrocities to a conflict between a few individuals, rather than between entire nations of people. In place of the terrorist attacks, Everett substitutes the brutal assault and murder of the narrator’s daughter, and the subsequent kidnapping and torturing of a man, who may or may not be the assailant, by the narrator. The narrator, identifying himself as Ishmael Kidder, enacts a sort of vigilante justice as retribution for his daughter’s unthinkable fate with little concern for whether or not his captive was the actual perpetrator of the violence. This clearly maps onto the much larger-scale vigilante attitude adopted by the United States government, which saw the deployment of troops and terrorization of masses of people overseas who were uninvolved in the attacks. The parallel is seen perhaps most clearly in the title of the book, referencing a torture tactic used by Kidder against his captive and by members of the United States military in places such as the infamous Abu Graib.

Just as fractal scaling has cost-benefit advantages in African design, Everett’s use of thematic scaling delivers an especially strong impact. The central purpose of scaling is to adjust a design to the conditions of what is required of it, as in how the repeating spiral structure of some animals’ horns is scaled outward to fit the animal’s growing head. The aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks is a period in the nation’s history that feels almost impossible to grapple with, due to the unfathomable scale of the destruction surrounding it. No matter how information on the subject is conveyed, it seems that plain discussion of it can never get us close to coming to terms with it in meaningful ways. Scaling the situation down to interpersonal violence is much more suited for gaining a deeper understanding of the moral and ethical questions surrounding it, doing two main things: first, by revealing how ridiculous the country’s response to the attacks looks in hindsight, taking the grief over one atrocity out on those possibly not even involved in it with a more prolonged campaign of violence; and second, by making room for more understanding of what the those in power to that decision, highlighting the broad range of human emotions that can be heightened in the wake of horrendously inhuman acts. Everett’s microcosm of what would end up being decades of conflict between nations serves to bring the real-world events closer to the hearts of readers than regular descriptions tend to. The scaled-down portrayal takes its scaled-down form to adjust to how most readers experience the world surrounded by such massively scaled violence.

Even if it is not conscious, people engage in scaling practices all the time to simplify their understanding of the world, and this can have more negative consequences than the mathematical and literary implications of scaling. As I have reexamined my time in this course, I have identified some scaling of my own that I have unconsciously exercised. Given that this course has essentially been a survey course in a literary tradition that I had previously had relatively little exposure to, I am acutely aware of a pitfall of scaling out a few pieces of literature as being wholly representative of an entire body of literature. Black art has a history of being systematically pushed to the margins of academia and of dominant American culture, and I want to play an active role in dismantling my own ingrained notions of black literature by seeking out more of it. However, amidst the noise of everything that the human brain must take in day by day, I believe there is a tendency to try to make it easier to understand the work by substituting large groups of subjects with mentally constructed overarching scalings of individual subjects. It would then be possible to take the experiences I have had in this course and the analysis of the works we have read and treat it as having fully immersed myself in the world of African American literature, and that the work of deconstructing my personal biases is already done. This is a substitution that I need to be wary of, as I know that my journey in educating myself is still towards its beginning, and that the ways of thinking that we practiced in this course must be habitually continued as an ongoing process.

Beyond my basic awareness of this concept, several of the pieces of writing we read and their surrounding context clearly displayed the consequences of this kind of substitutive scaling. For most of the history of the United States, the hegemonic cultural focus has been inundated with works created by and for white people. This partially arises from and feeds back into the systems of white supremacy that the country operates under, which only functions with the construction of dually whiteness and non-whiteness, where whiteness is viewed as the normal condition and non-whiteness is a deviation from the normal. Therefore, members of the “in-group” may often use things that they see from the “out-group” to make generalizations about them. Black American artists have thus been forced to create their work under the watchful eye of American whiteness, feeling the pressure of their individual works having the potential to be scaled out as representative of all black art for some audiences.

This is seen in the “Fugitive Slave Narrative” genre, where writers were pressured by white abolitionists to abandon the artistry of their storytelling and just focus on the plain facts of their enslavement, as their experiences would be taken by white readers as a picture of the whole of slavery, since reading these narratives was simpler than directly engaging with the reality of slavery.

Another example of this could be seen in our discussions surrounding Angles of Ascent, an anthology of modern African American poetry. Like all anthologies, it includes only what the publishers and editors feel should be included, giving the publisher a difficult task of deciding which poems and poets should act as the representatives of black poetry. This can cause conflict when there are differing views on what this material should be, as evidenced by the public disagreement between Amiri Baraka and anthology editor Charles Henry Rowell (A Post-Racial Anthology? by Amiri Baraka | Poetry Magazine). Such issues become more prominent because black creators are placed under more scrutiny and have their lives, works, and public interactions scaled to a magnitude different from their white counterparts.

Recognizing similar unconscious scalings and substitutions in my mind has been and will continue to be a central part of my work with this course. I have begun to notice times when I scale certain things down to a more digestible frame of reference to make myself feel more comfortable with things that are difficult to grapple with. Especially when confronting historic and current injustices against people of color worldwide, it can be tempting to avoid direct engagement as it is, but this only perpetuates and upholds such injustices. Scaling can be helpful in gaining a clearer understanding of moral ambiguities at a human level, but it also runs the risk of downplaying the gravity of a given situation. If I were to imagine the gruesome killing of a loved one, and imagine a scenario in which I respond by killing dozens of people uninvolved with the initial violence, this would not give an accurate picture of the all-too-real implications of when such conflicts play out on a scale of thousands. It is a long process to learn to see uncomfortable truths as they are, but I at least feel that this course has provided a strong groundwork for the process.